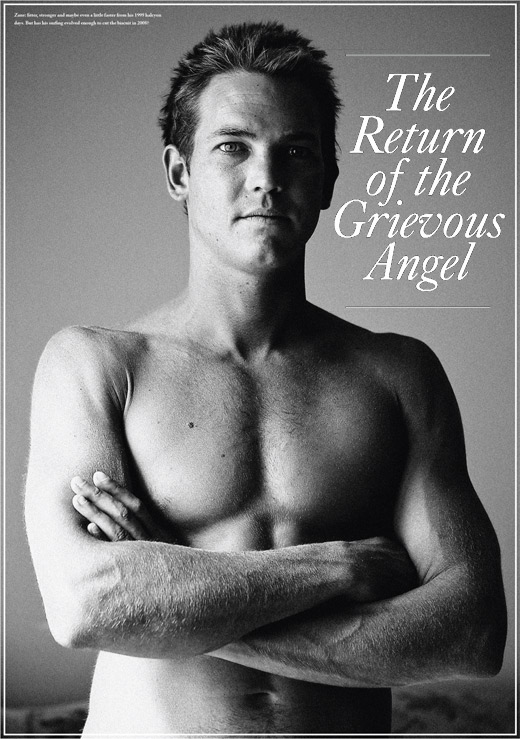

The Return of the Grievous Angel: Zane harrison

Fred Pawle visits Zane Harrison in an almost surfless town on the Queensland Coast, where’s he’s gone to forget about his past and to prepare for a dramatic comeback. All photos by Andrew Shield ane Harrison was working the drop saw on his dad’s building site when he heard on the radio that his former […]

Fred Pawle visits Zane Harrison in an almost surfless town on the Queensland Coast, where’s he’s gone to forget about his past and to prepare for a dramatic comeback.

All photos by Andrew Shield

ane Harrison was working the drop saw on his dad’s building site when he heard on the radio that his former rival, Mick Fanning, had just won a world title. He had stopped envying Mick long ago, but he didn’t need reminding that their fortunes had gone in different directions. Being a labourer gave him plenty of time to reflect on the issues that had led him from being the most famous teenage surfer in the world in 1999 to, well, a better surfer than you’d expect to find in an isolated town like Agnes Waters (population: 2500). They’re issues he doesn’t like to talk about much, even though he has deliberately and thoroughly dealt with them over the past two years. Fair enough, too. A past like his would hurt if you dwelt on it.

ane Harrison was working the drop saw on his dad’s building site when he heard on the radio that his former rival, Mick Fanning, had just won a world title. He had stopped envying Mick long ago, but he didn’t need reminding that their fortunes had gone in different directions. Being a labourer gave him plenty of time to reflect on the issues that had led him from being the most famous teenage surfer in the world in 1999 to, well, a better surfer than you’d expect to find in an isolated town like Agnes Waters (population: 2500). They’re issues he doesn’t like to talk about much, even though he has deliberately and thoroughly dealt with them over the past two years. Fair enough, too. A past like his would hurt if you dwelt on it.

He didn’t quite understand that it was my intention to dredge it all up when he agreed to let me come and stay one weekend in April, but to his credit he eventually lowered his guard to reveal how it feels to fall from such a great height, and what it’s taken to dust himself off for another crack.

The Qantas twin-prop taxis to the terminal at Bundaberg airport. Zane, now 27, is easy to pick amid the white-bread locals waiting to meet the other disembarking passengers. He still has the cute, boyish features that made him a walk-up start in chicks’ mags from the age of 16, but he’s more masculine – the blond hair’s cropped back to its dark roots and the skin, exotically tinted with his mum’s part-Maori blood, bears the early signs of decades under the Queensland sun. And he’s the only one wearing a Rip Curl T-shirt, a stack of which he’s still wearing these days, more than two years after they dropped him, mainly because he hasn’t got round to restocking the wardrobe with anything new.

We grab my gear and throw it in his Commodore sedan. It’s a 90-minute drive to Agnes Waters, the small town north of Bundaberg where he moved last July, so we pull into Macas to get a coffee for the ride. Somehow we’ve already started talking about the main topic I’m here to discuss – his battle with alcohol during the latter part of his time on tour – and he tells me he hasn’t touched a drop for 18 months. His demeanour so far hasn’t revealed anything remotely suggesting demons in this department, so I ask if he stopped because he simply grew out of the urge to get necked rather than consciously forcing himself to give it up. He looks at me with a sardonic smile, pauses and says, “I think it’s ruined my life enough already.”

It’s a bit early in the day for deep, dark conversations – and I’ve only just met the guy anyway – so we steer the chat back to lighter topics, such as his mixed but promising results on the recent Australian leg of the WQS, the difficulty of finding sponsors these days, and how good it’s been for him to move away from his home on the Sunshine Coast.

Ten minutes out of Agnes Waters, we pull into an isolated road stop so he can have a piss and pick up a chocolate bar. When he gets back in the car he’s still grinning from having had a little exchange with the bloke who owns the shop. A few weeks earlier, the local paper, the Gladstone Observer, published a story about a local surfer who had come ninth at the four-star WQS at Soldiers Beach, Newcastle. That same week, the bloke at the road stop recognised Zane from the story, and the two struck up a typically rural rapport.

For someone who once found fame so easily, Zane is at ease with this periodic publicity. Back home on the Sunshine Coast, he was constantly explaining to people why he, the kid who won Sunset in 1999 (beating Kelly in the early rounds on the way to meeting Sunny, Paul Paterson and Ross Williams in the final) and came third in that year’s trials at massive Pipe, had dropped off the tour. Here, nobody asks him about that. Instead, they want to know how his plans for getting back on the tour are coming along. And the answer to that is, very nicely, thanks for asking.

Zane and I pull up at his parents’ modern, three-storey house on the top of the highest hill in Agnes Waters. From the lounge room you get a perfect view of the beach, point and half the Pacific Ocean. If there’s waves, or even swell on the horizon, the Harrisons know about it. Both Zane’s parents, Harry and Muriel, surf, as does his younger brother Marcel, who also lives at home. The furniture is all white upholstery and cane, there’s an abstract painting of a tropical reef-break on the wall, and a decorative asymmetrical channel-bottom fish hangs above the kitchen cupboards. The ambience in the house is more like a shared surf shack than a family.

The point is looking tiny, so Zane, Marcel, his girlfriend Mel and I drive to a beach round the back, where a one-foot peak is breaking in a cove protected from the howling southerly. The surf up here lasts from December through to about May, and Zane’s rule of thumb is that if it’s four foot back on the Sunshine Coast, it’s one foot up here. This suits him just fine.

Zane proved as a teenager that he’s got big waves covered, so for now he’s working on his small-wave repertoire, which is all he’s going to get in Agnes Waters anyway. Some days he sets up a video camera on the beach with a 45-minute tape in it, and paddles out and catches as many waves as he can. He laughs when I tell him he used to have a reputation for not having a decent forehand cutback. He can afford to laugh; from the way he bounces his Bourton off the whitewater like it was made of foam rubber, I can see he’s got one now.

Walking back up the beach, he tells me that the Sunshine Coast beach breaks in which he grew up forced him to develop mostly vertical moves, which he thought the judges on tour would love. But it was open-face “hackbacks”, as performed by his peers from the points Mick and Joel, that the judges loved more. He theorises that this might have something to do with the spray from carves being more spectacular to the big non-surfing audience, which seems a reasonable argument to me. Nevertheless, he’s happy to go along with the criterion, and surfing Agnes Waters’ two uncrowded point breaks – when they break – is now the perfect training ground for him. “I can do turns over and over again till I’ve got them right,” he says. “And every day I’m learning.”

Back at the house, I get him talking about how things fell apart last time. It started with a fun surf at Maroochydore in January 2001. Zane swapped his board with a mate’s home-made seven-footer. He busted it out of the lip and landed it awkwardly with his front leg fully extended. His knee locked, and the jolt drove his leg into his hip. In serious pain, Zane immediately paddled in and limped up the beach.

A week later, at the start of the 2001 season, he entered the WQS event at Snapper. He kept winning heats, but the pain in his hip increased with each round. By the time he made the final, he could barely walk. The other finalists, Occy, Mick and Taj, did the run-around between waves. All Zane could do was catch their leftovers. He came a “convincing fourth”. He was in agony, but he told himself, not for the last time, that things couldn’t be too bad if he was making finals.

For seven months he travelled the WQS, seeing doctors wherever he went, trying to get a diagnosis on the pain that just wouldn’t go away, which was preventing him from walking further than 200m at a time. “I was walking into the surgery, so they must have thought there wasn’t much wrong,” he says. One sport specialist concluded that the problem was muscular, and did some physio – wrapping straps around his thigh and pulling his leg outwards – that, in hindsight, surely exacerbated the injury. When that doctor’s prediction of recovery in three months failed to eventuate, Zane went to another doctor, who sent him off for x-rays. Finally, seven months after the initial injury, the culprit was identified: a hairline fracture in his pelvis. The bone specialist to whom he took the x-rays was shocked. These injuries are often suffered by motorcyclists who’ve crashed and slid leg-first into a kerb, but never by surfers. Zane was told to stop surfing, buy a pair of crutches and stay off his left leg for at least seven months. He didn’t. He went to Hawaii, taking the crutches with him, but not using them much. All he had to do was make it through his first heat at maxing Haleiwa and he would have qualified for the WCT. He came third.

Back home on the Sunshine Coast, bitterness kicked in. “When you lose something that you love so much, and you’re sitting at home listening to your peers’ results, stuck on the couch, and there’s nothing you can do about it… I was definitely really depressed,” he says. “I thought life was out to get me. I was down and angry and hating life.”

Rip Curl stuck by him, but that was the silver lining of a dark cloud that was gathering into a storm. Things were going to get a lot worse before they got better. At this stage, he was still confident that he could bounce back quickly. In fact, he did, coming second to Bruce Irons at the Gotcha Pipe event in February 2002. But the hip hadn’t healed, and he was sentenced to another six months on the couch and hobbling around on crutches. He would change the treads on those crutches more than 20 times before he finally threw them out a couple of years later. In late 2002 he had to learn to walk again because his leg was emaciated and his back was twisted from the lopsided way he got around.

On the occasions when he ventured out of the house, people would constantly ask him why he wasn’t surfing any more. The answer became tedious. Beer, the tonic that had been nothing more than a social lubricant in his earlier days on the WQS, emerged as an antidote to the boredom and pain. “I started drinking a lot,” he says, “trying to numb it out. You end up questioning everything, and why you’re drinking. It’s a vicious circle.”

Sitting on the sofa at his home on the Sunshine Coast, he’d crack his first for the day mid-afternoon. His girlfriend Amber, an increasingly successful real estate saleswoman, would come home from work to find him half cut and embittered.

He did sporadic attempts at the WQS in 2003 and 2004, developing ways of walking that disguised his limp, especially when he was in Victoria, around Rip Curl staff. By now, though, the drinking had become a major part of his routine, and binges were being triggered more and more frequently by his early departure from events.

More than most pro surfers, Zane takes losing badly. “It became a way of life,” he says, “not doing too well in heats, then just going…” He thinks about it for a while, and quickly goes circumspect. “In surfing, you have high highs and low lows.” Yes, but either way you wind up on the piss, I add. “Yeah, that’s pretty much it. Everyone does the same thing.”

Well, not exactly. Zane followed a different pattern to the one most pro surfers had followed since the early 1980s. He wasn’t getting necked for fun.

“He wouldn’t go out and party,” says Troy Brooks, who travelled with him throughout their Junior Series and WQS days. “When we first went on tour he’d come out to the bars and stuff, but towards the end he’d come out maybe once a year. He’d come to dinner and have a beer, but then he’d go home and drink, whether it was by himself or with someone else. That was the cycle he was in.”

Troy says the problem got serious in France in 2005, where he and a few other WQS surfers were sharing a house with Zane and Amber, who joined him for part of that year’s tour.

Troy went out to buy some milk at 8am one morning. Before he left, he checked if there was room in the fridge, and noticed half a dozen beers on the shelf in the door. Ten minutes later he returned, and two of the beers were gone. Amber was in the shower. Zane was in the dunny. Troy waited, and confronted Zane. At first he denied it, but Troy found the empties Zane left behind, the glass still cold.

“That was the first time he really wanted to hide it,” Troy says. “That’s when I realised he had a problem. I just wanted to grab him round the neck and shake him out of it.”

Troy and Jarrod Howse hunted down some info about alcoholism on the net and cut-and-pasted it for him to read. “I figured that if he sat there and read it he wouldn’t feel under as much pressure if one of his peers was lecturing him,” Troy says.

Zane was quick to accept that his drinking wasn’t normal. He got off the piss for four days, and the effect was immediate. Suddenly his surfing was back, and everyone noticed. “It was the best I’d seen him surf in years,” Troy says. “He was landing air-reverses, looking so fresh.” But he ended that with another 15-beer binge, and lost another first-round heat the next morning.

Zane was under a lot of pressure. Rip Curl was on his back about his rating, his hip wouldn’t heal properly and, deep down, he knew Amber wouldn’t hang around forever. Despite what he’d seen, Troy wasn’t sure if Zane was a born alcoholic or merely reacting to a severe case of stress. “It definitely was a depressing time for him,” Troy says. “Most depressed people hide shit anyway. He was still smiling and stuff, you never know what’s really going on.”

Zane says the hip finally healed at the end of that year, but by then it was too late: Rip Curl had to let him go. That was the nadir, but, as Rip Curl team manager Gary Dunne recalls it, he was man enough not to blame anyone else.

“He took it on the chin,” Gary says. “He even said, ‘thanks for the opportunities you’ve given me, and for supporting me’. He was clearly disappointed, but he’s a pragmatic young man. He understood we’ve only got so much money to throw around, and he’d been going backwards for three years.”

Ironically, Zane made an indirect but significant contribution to Mick’s eventual world title. “We learnt a lot from what happened to Zane,” Gary says. “When Mick hurt himself (a career-threatening hamstring injury in 2004) we were much more proactive rather than passive in connecting him with the best medical advice.”

Zane, despite being fit to surf again, let his boards gather dust while he sat on the couch, cursing fate. Amber left in 2006. “I knew it was coming,” he says with a self-deprecating smile. “I brought it on myself.”

+++++++++++

Zane spent 2006 exorcising the bitterness and jealousy from his head. Halfway through 2007, he made the move to Agnes Waters, took up a job with his dad, and started planning his comeback. At the start of this year, he hooked up with Grom, the owner of the town’s only surf shop and the most overt-looking hippie in this otherwise middle-class hamlet, as his coach.

They’re an odd couple. While Zane is cautious and reticent, Grom can happily ramble in conversation from, say, the demographics of pro-surfing fans to the pros and cons of small-town politics. But, during my quick chat with him on the verandah of his home down the hill from the Harrisons’, I discover there are some topics about which he is unequivocal.

While Zane sits quietly, Grom tells me about the tough two-hour training sessions he’s had Zane doing five to seven days a week most of this year. Zane pushes himself throughout the sessions, which consist of sit-ups, push-ups, paddles, heat drills and sandhill sprints. At the top of the sandhill, Grom’s got Zane practising his claims, Rocky Balboa-style. If he’s going to start winning again, Grom says, Zane’s gonna need a bit more mongrel in his phsyche.

“You can be too humble in life,” Grom says. “Sometimes you gotta go, ‘yes! I deserve this! I’ve done the work and I deserve to be at the top’. You gotta be able to use it but not abuse it. You can’t go through life waiting.”

Later, Zane talks down this need for bravado. “I just go out and do it,” he says. “You’ve probably heard time and time again people talking themselves up.”

Actually, no, I say. Pro surfers are far more reluctant to talk themselves up than most other sportsmen.

“I guess we’re just quiet achievers,” he says.

If anything is motivating him, other than the obvious fact that he left without realising his early potential, it’s Grom’s faith. “I just want to do it because he’s got belief in me,” he says.

His dad, Harry, is another believer, providing other crucial support, such as a job and a salubrious roof over his head while he’s on the comeback program. “He’s got a lot of natural ability, but we’ve always had the philosophy that the more he trains the better he’ll be. It’s all about the preparation. He can’t just have a crack at it and see if he can come back, it’s got to be all preparation, so that when he does go into a competition he doesn’t have to worry.”

The target is to requalify by 2010. The immediate goal (which, thanks possibly to Grom’s encouragement, he’s happy to share) is to make the final at the Maldives six-star, if he can get a start in it. A couple of minor companies started sniffing around after his ninth at Soldiers Beach, but he’s not courting sponsorship deals until he’s proven that he’s got what it takes to make a full comeback. “Knowing what I know about the tour, I’m going to be serious this time,” he says. “Everyone’s got their head switched on now. It’s going to be a good fight, that’s for sure.”

Zane’s not the only member of the Rip Curl family to have scoped the laidback surf vibe of Agnes Waters. Claw Warbrick recently bought a prime chunk of the point where we surfed that afternoon. Zane saw him in the water up there only a couple of months ago, and naturally dropped a hint. “I told him I was giving it a go, and he pretty much said we’ll see it when it happens,” Zane says.

“I’ll never say never to someone like Zane,” says Gary Dunne. “You don’t win the World Cup at Sunset as a teenager without talent. We always felt he had a big future. His results as a junior were fantastic, at a time when the crop was hot, then the injury held him back. But he’d have to produce some extraordinary results (to be re-signed).”

++++++++++++++++++++

Unlike every alcoholic I’ve met (and there’s, ah, been a few), Zane doesn’t have the awkward self-consciousness that comes with being born a six-pack behind the rest of the world. Neither does he rationalise the past, despite having more reason than most to do so.

The attention from chicks’ mags was not for nothing. Zane reluctantly confirms that he was never short of offers, even by pro surfer standards. “There was always a lot of eyes on him,” Troy says. Even two years ago, his surfing career in tatters (but officially single again), Zane managed to make Cleo’s 50 Most Eligible Bachelors. But he doesn’t overstate the value of it. “I’m glad to have had those experiences,” he says. “Life was shitty in some ways and great in others. The problem was that even though I was getting a little bit of love I was still feeling shit in the morning. I mean, the ladies weren’t winning contests for me. I wish I could take all those years back and do what Mick did. But then, he was no angel either.”

When Zane heard that report about Mick’s title win on the radio while working on the building site last November, it was a kick in the arse. “I knew how much work he’d put in,” he says. “And he deserved it. It was great to hear that one of the guys you used to compete against had won the world title, you kind of feel you’ve been there as well.”

Did you think that if he can do it, so can you?

“Not so much. I haven’t trained as much as he has. But I know in time that might change.

“I’ve got a lot to prove. I didn’t give 100 per cent before, but I know I will this time. You don’t have many chances in life, and to even have this chance to go back, to have my health, to feel as fit as I do, is a blessing.”

Zane’s focus on the future emerges again later, after we pop down for a dusk session in Agnes Waters’ version of pumping one-foot windswell. Driving back up the hill, I mention that the edition of Matt Warshaw’s Encyclopedia of Surfing that is on the coffee table at the family home, doesn’t have an entry on him, despite him being one of only a few people to win a major event in Hawaii as a teenager.

“Yeah, it doesn’t even list me in the Sunset winners. For some reason they list all the winners, but no one for 1999,” he says with a bemused smile. The absence of even the slightest resentment in his expression is noticeable. “It’s like it never happened.”

I get the feeling he thinks that about a lot of things these days.

Comments

Comments are a Stab Premium feature. Gotta join to talk shop.

Already a member? Sign In

Want to join? Sign Up