A Long Overdue Look Into Black Surfing And Aquatic Culture

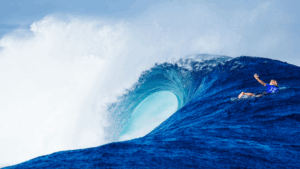

A deft new documentary explores the past, present, and future of Black surfing.

Does anyone remember those rogue commentators during the Surfing event at the 2020 Olympics?

It went something like this: “Who the f*** surfs in a typhoon? Well, I’ll tell you who doesn’t: black people. Do we have any footage of any black surfer that still went? As a matter of fact, this just in, every black surfer pulled out after they found out the typhoon was actually active. There were no black surfers on the Delta Airlines flight to Tokyo.”

Yes, the guys who said this still have jobs, and we might even see them again as (unofficial) commentators at the 2024 Paris Olympics. If you feel this was in poor taste, please address your concerns to Kevin Hart and Calvin Cordozar Broadus Jr., also known as Snoop Dogg. We’ll get back to you with their PO Boxes.

Though he was clearly joking, Hart’s faux-commentary highlights a real issue — the lack of black surfers being heralded on the world stage.

Hart was simply riffing on the old stereotype that black people seldom exhibit enthusiasm for water sports (or seemingly dangerous/unnecessary “white people” activities like storm-chasing). It’s an old farce, ripe for poking fun at in the right instances by the right people, but it is also unfair and untrue. This is exactly what David Mesfin’s new documentary, Wade into the Water: A Journey into Black Surfing and Aquatic Culture, hopes to dismantle.

There is little mainstream cultural imagery of black surfers. However, according to the documentary, wave riding and beach culture have been a part of black history for hundreds of years, despite the efforts of the morally corrupt both in the lineup and in government.

The award-winning film, airing now on Amazon Prime, PBS Hawaii and Vimeo+, traces multiple strands of the history of ocean culture in Atlantic Africa and the experiences of black surfers on the US West Coast from as early as the 1940s. It’s an astute, carefully woven telling of what to many of us is a veiled history.

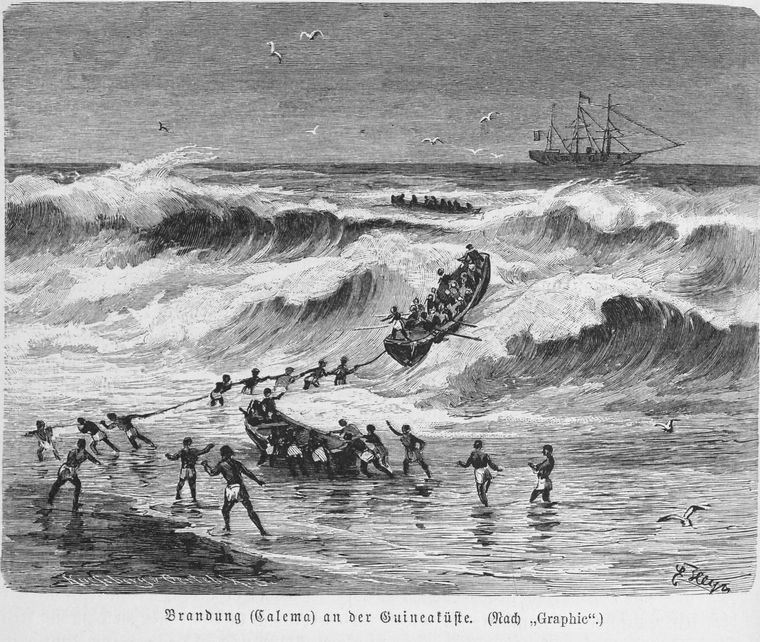

“The first account of surfing in Africa was written in the 1640s,” says Prof. Kevin Dawson, Associate Professor of History at the University of California. “Surfing is a 1000-year-old African tradition. The sport was independently developed from Senegal to Angola.” Some of the written evidence supporting this includes the notes of a German colonist who saw African parents tie their children to wooden boards and throw them out into the surf in 1640.

Europeans would continue to write home about wave riding in Africa for hundreds of years. One poetic account from 1876 describes, “…with light boards under their stomachs. They waited for surf and came rolling like a cloud on top of it.”

It’s not hard to imagine — consider the vast African coastline. With a sea-based culture, long wooden fishing boats, and endless Atlantic surf, it wouldn’t have taken long to figure out that riding waves back to shore is an efficient way to bring home your haul. It’s also undeniably fun, so why wouldn’t you do it again on a smaller piece of wood?

Professor Kevin Dawson also points out that being an adept wave-rider in Atlantic Africa is as much a necessity as it is a joy. The lack of natural harbors meant the only way to travel by sea was from the beach, which required Africans to be skilled with surf canoes all year round when navigating Atlantic beach breaks for fishing and exchanging goods.

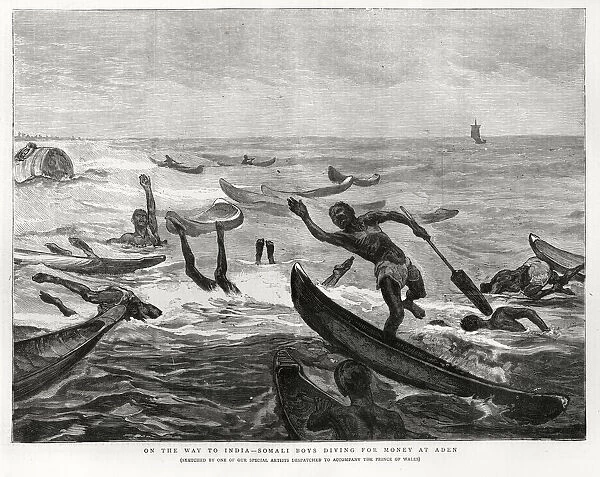

This aquatic culture survived the Atlantic slave trade, with enslaved Africans continuing their diving, fishing, and wave riding in the Caribbean. Enslavers soon realized that this oceanic aptitude could be exploited, forcing the enslaved to dive for sunken European gold during hurricane season. Sadly, much of this retrieved wealth funded more slave plantations in mainland America, as the film points out.

So why the stereotype? Is it simply a lesser-known history, that this entrenched symbiosis between African cultures and the sea just isn’t common knowledge? Partly. But the film highlights a much darker reality.

When descendants of slaves moved west to American coastal zones, they were socially, legally, and economically excluded from the beach culture that came to define the area.

The film profiles a young black American by the name of Willa Bruce, who opened a club on Manhattan Beach in 1912. It served as a dance hall, cafe, and lodgings for African Americans wanting to enjoy beach culture, where they were otherwise legally forbidden by segregation laws.

Even though the beach club was a legal business, irate locals tried to rope off their access to the beachfront. When the community persisted, locals sought out the KKK to run a telephone campaign of intimidation to force them out. This small black community continued to use the ocean and build their membership until real estate laws and profit motives found a final way to force them out.

In the 1920s, the US government seized Bruce’s Club under eminent domain law, meaning the oceanfront property would be taken, supposedly for public good. Of course it never was. In fact, the property remained dormant for decades, sending a clear signal — the beach was not for black folks.

This is just another chapter in the long, sad history of American land use. The roots of African American beach culture, and whatever surf talent it might have produced, were stifled early in its germination. Maybe the stereotype, “black people don’t swim” — and by extension “black people don’t surf” — is really just a cheap obfuscation of the cold reality that “black people weren’t allowed to swim”, and “black people weren’t allowed to surf.”

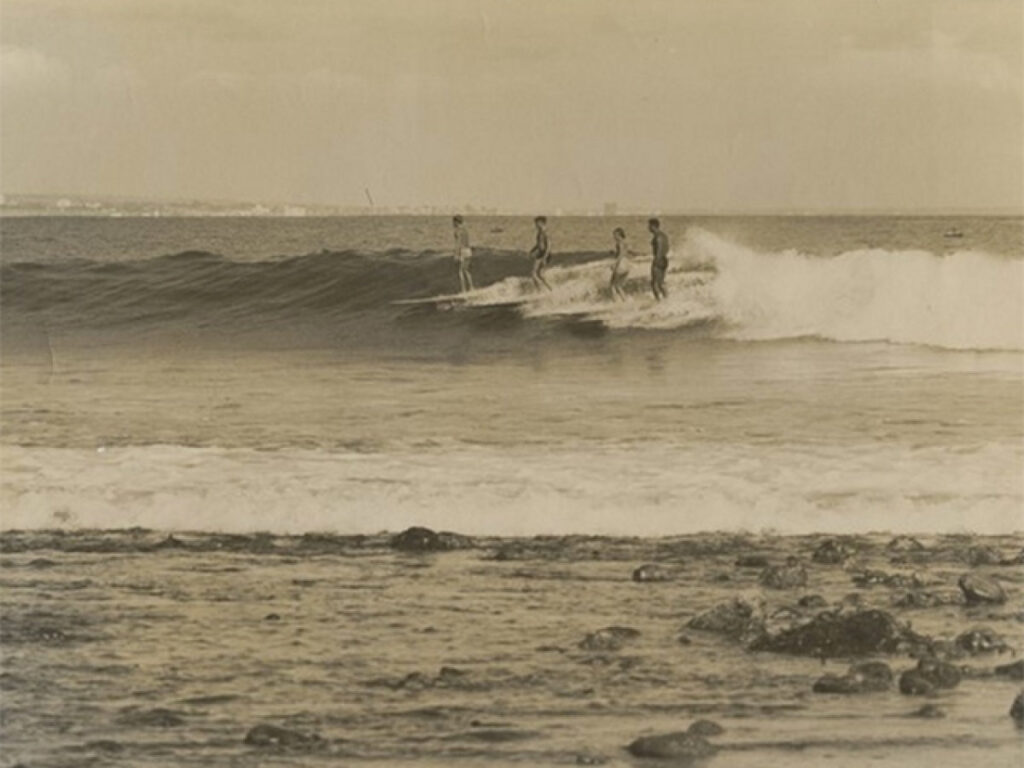

But, as the film celebrates, they did anyway. Even in the 1940s, before the word “racism” entered the US government’s lexicon, a young Nick Gabaldón was borrowing boards and teaching himself to surf in front of Bruce’s Club.

The half-black, half-latino surfer got good quickly, and became known for paddling 12 miles from Santa Monica Bay to Malibu to surf. Gabaldón, who tragically died while shooting the pier at Malibu, is now recognized as California’s first black American surfer. A plaque at the once-segregated ‘Inkwell’ beach (derogatorily named for its black beachgoers), commemorates his contribution.

From Gabaldón onward, black surfers were there. We’ve all seen the footage of scrawny white kids with balayaged ‘70s bobs on plank skateboards on their way to the beach, single fins in tow, but the film is loaded with nostalgic Super 8 images of black kids doing the exact same.

It strikes us that these are the exact cultural images that seemed to be missing, as if frozen in celluloid and abandoned in a box at a warehouse. This is precisely where the value of the film lies — if there is a lack of cultural imagery of black people surfing, here’s a whole trove of it.

These groms, older now on camera, recount the unconscionably disgusting behavior they faced when the cameras weren’t rolling. Still, it doesn’t stop them from talking about those days with a certain fondness, that familiar twinkled gaze when an older surfer reminisces about how good the point was back in the day, before the crowds.

The film lands as a testament to resistance and rebellion, those two feelings that we sometimes forget started this whole surf business. But more than that, it’s a testament to surfing itself — that the attraction of riding a wave proved stronger than the cultural (and often legal) repulsion around it.

Suffice to say, watch the fucking movie. Surfing as a lens to trace the treatment of peoples according to their skin proves prismatic — it shines multiple lights on different strands that connect the sport’s history to the history of a people.

So, did we get you with our opener? The whole Tokyo Olympics bit? There’s no better way to unpack what is essentially a complicated and sad subject, than with some humor.

Even if it is Kevin Hart’s.

Comments

Comments are a Stab Premium feature. Gotta join to talk shop.

Already a member? Sign In

Want to join? Sign Up