Beyond The Fedora: How Fernando Aguerre Became Surfing’s Master-Puppeteer

From DJing and ding repair, to law and Reef girls, to the Olympics and beyond.

You’ll know Fernando Aguerre. Or at least, recognise him.

He’s the raspy voiced, wiry man in bright shirts and bow ties handing out golden tickets to the greatest show on earth. You’ll have seen him at the water’s edge at a boulder point in Central America informing elated surfers that they’re about to represent their country on sport’s biggest stage, or at the centre of a swirl of vibrant flag waving pageantry, somehow conducting the entire orchestra on vibes, beaming out from under half a dozen leis. He’s the one degree of separation between the He’e Nalu of the ali’i and Zeus’s Olympia — a man who’s made it his life’s work to do what most people considered impossible, and not an insignificant sector who identify at the core of surfing viewed with varying degrees of apathy.

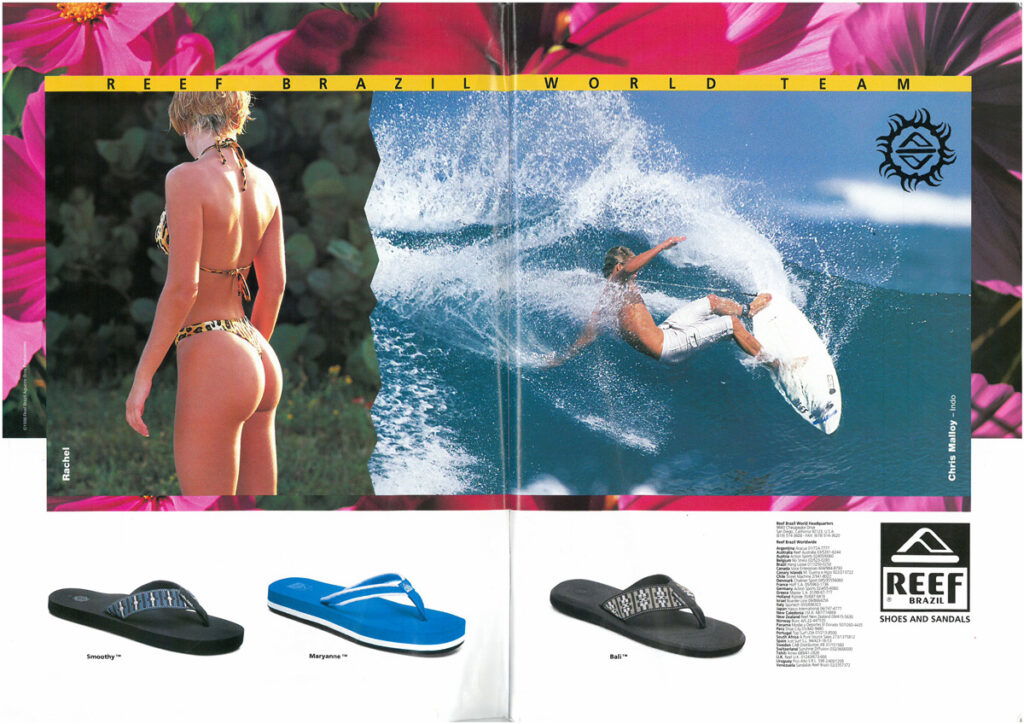

“A lot of people know me,” he says, “but don’t know about me.” Raised in Argentina’s Mar del Plata, surfing and entrepreneurship paired from an early age, he started out doing ding repair, DJing and organising beach parties. Later he opened a surf shop and qualified as a lawyer before moving to the US and founding Reef with his brother Santiago.

Competing for Argentina as a longboarder in an ISA event in Lacanau, France, in 1994, Fernando noticed that other continents had more cohesive federations — an ad hoc decision was made to found the Pan American Surfing Association over dinner one evening, and that he should run it. At the following ISA event, somebody nominated him for ISA president, and after initial reluctance to accept the nomination, he won the vote.

“I got sent a 30 x 30cm cardboard box that was all I got related to the ISA: a few papers, a bank balance of $5,000. Other than that, there was nothing. No logo, no real identity, no trademark registrations. The ISA was not incorporated in any country. There was nothing in place, so I thought, ‘I can’t really go wrong. Anything we do from here is a plus.’”

Soon enough, Aguerre began implementing structural changes that, with the benefit of hindsight, now appear visionary. In 1996, a deal was struck with the ASP to rename the ISA events Games rather than World Championships, with the ASP’s top stars being allowed to surf in them in return. The ISA World Surfing Games would feature a parade of nations, awarding individual and team medals rather than trophies. Aguerre had seen the big picture, and it was distinctly five-ring-shaped.

If surfing’s two-and-a-half decade journey to securing Olympic status is one of perseverance on Fernando’s part, what’s less clear — particularly when you consider he’s never been paid a cent to do it — is why.

“I just thought that for a sport that has done so much for people like me, that it would be nice to share it,” he says. “As a lifestyle, surfing is a cure for most of the illnesses of modern life. I like the sense of creating community, I love looking at unassembled things and putting them together. So when we sold Reef in 2005 and I asked myself, ‘What do I do now?’ I decided it was time to push harder for this Olympic thing. At that time, most people at the IOC simply didn’t understand what surfing was.”

Despite having founded and run one of the most recognisable brands in surfing (and currently being one of most influential administrative/political figures in surfing history), Aguerre still seems to identify as something of an outsider. Hailing from a relative surfing backwater in Argentina and maintaining a leftfield take from some of surfing’s major institutions and gatekeepers has been key to his worldview.

“I was looking where nobody was. The pro tour was just focusing at the very top, but nobody was looking at those nations that may be at the top in the future, and how they could get there.”

As mad a fever dream that surfing as a permanent Olympic sport sounded two decades ago, it would’ve seemed even less plausible that Chopes 2024 would feature tube-seeking Olympians from China, Israel and Canada.

For all Aguerre’s forward thinking, there’s something faintly retro in his storytelling. Rather than adopt the excruciating modern management speak of a high performance podcast host in executive sneakers — one of ‘authentic journeys’, ‘performance pathways’ and ‘outcomes’ — Fernando carries an unashamedly up front Boomer surf vibe. A setback becomes a “wipeout”, an opportunity “the next set on the horizon”. It might hint at an understanding of the importance of a broad base appeal, or maybe simply of elapsed time.

Since he’s been out campaigning to bring surfing to the Olympics, our public perception of the establishment has shifted. There’s a broader cynicism toward institutions and governing bodies, a backlash against internationalism and perceived political correctness. It’s not just that Fernando realised an unlikely dream, but that he sustained it under radically shifting social norms.

If Tokyo put the frighteners up certain sectors of core surfdom — that as soon as the global Olympic audience found out about it, they’d suddenly be swarming lineups to saturation — it’s been hard to directly attribute any major impacts so far. And while most of us were wondering how Olympic inclusion would bend surfing, Aguerre’s focus on the inverse has been key to his success in positioning the sport.

“We bring a lot of value to the Olympic movement — I think we did in Tokyo, and will continue to do so.” Perhaps it was less about surfing getting its big break, and more about a staid, 130-year-old institution of blazers, tape measures and stopwatches leaning toward the light of relevance.

“It was our idea, but we had to convince them, and it took us a while to explain why,” Aguerre says of the decision to stage surfing 16,000km from Paris. Teahupoo is the most spectacular, photogenic wavescape on the planet, but also one of the most logistically challenging — and deadly. Surely in terms of scheduling, broadcasting and athlete wellbeing, a Parisian pool would’ve been a safer bet?

“The pool idea was shut down by Paris a long time ago. Even if somebody had already built one, they weren’t going to use it. They wanted to do it on the ocean.”

With the exception of Melbourne 1956 when equestrian events were held in Sweden due to quarantine rules on horses, never before has an event been staged outside the host continent.

“We had to push the rules to take it to Tahiti. An international federation (in surfing’s case the ISA) runs each event at the games, not the IOC or the organising committee. But while the federation has a role in selecting the venue, ultimately they needed convincing [to go to Tahiti]. There are challenges of course — we won’t be at the opening ceremony in Paris, but we’ll still be part of it, broadcast live for all the world to see.”

The infrastructure legacy and financial burden left behind in a host city remain one of the most scrutinised aspects of staging the Games. Montreal took four decades to pay off the debt of hosting the 1976 games, Athens 2004 became infamous for its taxpayer-funded white elephants, hundreds of millions spent on stadia left to fall into ruin after a few weeks’ use. But the Teahupo’o tower controversy seems to have been largely resolved via consultation and compromise, and Aguerre is not overly concerned about irreversibly altering the relatively pristine, underdeveloped nature of one of surfing’s most iconic venues for just four days of heats.

“I don’t think Tahiti will change that much. We’re arriving, having a party, a sports celebration, then we leave and the place goes back to what it was. But it’ll certainly put it on the map. Overall, people there are excited, one main source of income there is tourism. It’s not just about Teahupo’o, because only a tiny percentage of surfers are skilled enough to handle that wave — it‘s about promoting all of French Polynesia as a beautiful destination.”

Whatever the cultural impact of 2024’s Olympic surfing (likely to depend on how epic or otherwise conditions are) a largely favourable ISA approval rating feels like a rarity in our sport — one of ever dwindling, asset-stripped big surf brands and a professional tour not without its detractors.

“The ISA is not a corporation or a business — it’s a foundation. I guess people love seeing other people doing things for love,” Fernando explained.

Having so far failed to secure surfing’s inclusion for the Paralympics this summer or for LA 2028 — who opted for climbing instead — Aguerre’s resolved to “paddle back out” and try again for Brisbane 2032. You’d have to fancy his chances of eventually succeeding.

”There’s always wind against you when you’re moving,” he says. “But I’m quite persistent.”