Getting To The Heart Of The Matter, With Bruce Irons

“I have dreams that are new, as if he’s still here. We’re still young, fighting. He’s getting me mad. I wake up mad. Like, You’re still doing this to me? And I wake up sad a lot, missing him.”

It was a sweltering Southern California afternoon, the sky cloudless and bright blue, the wind dead at noon and the air stagnant, a little choked, as I drove past the throngs gathered at the Huntington Pier for the US Open, heading across Newport Harbor to meet Bruce Irons.

With his young children living full-time in California, Bruce was hanging at his old friend Logan Dulien’s pad, a familiar abode where Irons spent summers as a kid, surfing NSSA comps with his big brother, Andy, “running wild,” as Bruce says—just young kids from Kauai with the whole, huge surfing world right at their fingertips.

A lot has changed in the twenty years since Bruce and Andy’s teenage arrivals. When we talked, Bruce was fresh off a grueling and emotionally draining run of interviews, filming for the documentary on his brother, Andy Irons: Kissed By God, directed by the Jones Brothers, which premiered last night in Los Angeles.

Bruce and I sat down on his Newport balcony, and started at the top, with Bruce as bright and clear-eyed as I’d seen him in years, looking trim and in fighting shape, thoroughly reunited with his first love, surfing.

Bruce was getting back that feeling he first found as a young towheaded grom on Kauai, which was where our conversation started.

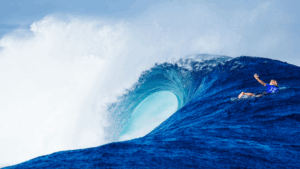

Bruce Irons, North Shore, 2017.

Photography

Max Reyes

Stab: So tell me about growing up on Kauai and those early years surfing with your brother.

Bruce: Man, even back then, Dad would pack us up on a Friday, and ship us off for the weekend to Oahu. 25 bucks, boom boom boom. You had to go to Oahu to surf, or for contests. We’d see everyone we grew up with—Makua, Jamie, Kai Henry—all the boys from all the islands at any contest we went to, and it was like that ever since we were like 12, 13. Just, groms.

Then, we came to California. I started riding for Volcom when I was probably 13, and Troy (Eckert) had a house at 54th street, and I would come and stay with them. That was how I first met Logan [Dulien], actually. At that house. We went through many stages of life in that house.

You ever hear of the Wreck Room? A lot of, let’s say, memories. Good, bad, ugly, all of it. This goes back years. The Wreck Room days [laughs]. Those were the days.

What was that like being that young, growing up so removed from all this, and being thrown right into the belly of it all?

Back then, it was sick. Volcom was a new company, it was fresh—and it was right here [in Newport Beach], you know? Everyone was so young and they weren’t so serious, nothing was square.

But coming here after growing up on Kauai, just being young kids, running wild, surfing, having a good old time. It was so exciting. To be that far away from home at that age, and on your own, with so many other young people… I mean, I think Troy was like 25. We were all just kids. We were getting to go on these amazing trips, filming for Magnaplasm.

Was that your first big film project?

Yeah, that was the first movie I did with them. I don’t even know how that movie came about. That was back when we still were shooting film, so we had no idea what we had. You know, we’d take a trip and surf and we wouldn’t even think about the filmer—they were just another character on the trip. And Brad Doherty was the ultimate character. One of a kind.

But we never got to see anything until it was done, so we’d just travel around the world filming, just having a blast.

Magnaplasm was a really special one for me. That premiered at the… uh, I think it was at The Grove…They used to have Surfer Poll there. Or, The Galaxy? Upstairs ballroom, like opera-looking shit. The Galaxy Theater. That’s it.

We were raging. I was, I think, shit—18, max. That was the first real movie I was involved with.

At the time we were doing it, I never thought it was anything bigger than it was. I was just surfing with Gavin and the boys. Looking back at it now, that movie is just so cool. It had a vibe that carried you through the whole movie, and a lot of that had to do with how hands-on Richard [Woolcott] and Troy were. They made all their movies in the beginning. They’d hole up in Woolie’s trailer for fucking two weeks straight, just editing, pasty white, never leaving, just losing their minds.

But coming away with gold.

That early Volcom team always stood out to me as one of the first really interesting teams entirely made up of freesurfers, and just such a crazy diverse group of styles—Chava, Punker Pat, Gavin. You were honestly the closest they had, really, to like a mainstream name or a contest guy.

Yeah, at that time I was still doing contests. After you surf Nationals, back then that was what you were supposed to do. It’s not like it was today, where you’re starting from a younger age.

Back then, we’d do Nationals as seniors, then graduate, and we were all like, Holy shit, I’m starting to get paid to travel, to qualify?

Did you always want to be on tour?

I never thought I was going to be a pro surfer. I never thought I was good enough to do that, to make the tour. That was what my idols were doing. That was just a daydream I’d have. I was just surfing.

But your brother didn’t feel that way.

Fuck. No.

He was always psyched, and I was a lot more da da da— I never wanted to be that serious, I was always more just, Fuck it, I’m going with the flow.

I didn’t really care about it, but I was going to the QS because it was what I was supposed to do. I didn’t understand anything about points. And of course here’s my brother, just calculating. And I was like, What the fuck?

“I can tell a true friend when they come up to me—and say it’s been six months, eight months, whatever, and they’ve heard what shit people are saying—a friend will come up and look at you and ask you, How are you doing? He’ll look you in the eye, grab your hand: You good, man? Yeah, I’m good.”

Photography

Max Reyes

I mean, you guys were way before the time of like, coaches and shit.

We didn’t have coaches, fuck no! We were kids. Me and Gavin were going to Argentina for a surf contest, and it was like, you know, waist high. I’m 17, Gavin’s around the same. Yeah, like Gavin and I were about to get real serious in that.

We were just taking it in, seeing new places, having fun. That first year, I went to Argentina, Uruguay. I’d gone to Australia a few times when I was young, for contests, or filming. But when I graduated, poof, I was gone. France, Brazil, Africa, Japan.

So I never really thought I was going to like make the tour, but I was so psyched to just travel.

Were you sort of just going through the motions in events, or were you having a hard time putting it all together?

I’d try, but not really. I was losing and getting pissed. After the third or fourth year, I was really struggling, in Portugal or Spain, flying in from a trade show somewhere, losing first heat, just a long drive heading back to the airport, no cell phones, looking for a payphone to call my dad, saying, I’m fuckin over this shit.

I was cracked. It was breaking me.

And of course, he’s all, Nah, nah, nah, nah, nah, nah… This is what you’re doing.

And I just thought, Fuck. This.

But I gotta give it to Woolly [Richard Woolcott]. Inside, Wooly is a competitor—a structured competitor. He’s precise. He’s calculated. He’s straight down the line. And he always pushed for me to think that way.

Wooly was a really good surfer. He was on the US team. He was a good competitor. And then he snapped his neck and that changed his course, so I always knew that inside he always had that passion for competing. And he wanted to see me take advantage of what I had.

So that was around the time you were working on The Bruce Movie. That’s such a massive movie to a lot of guys who were growing up back then, but in hindsight, it must have been such a heavy year.

Fuck—The Bruce Movie.

I’ve honestly only watched that movie a few times. It’s really hard for me to watch a movie about myself, you know? Or, it’s just, I don’t know.

At the time, I was really focused on making the tour. My brother had won a fucking World Title. And we were filming while I was qualifying, and my surfing was becoming really contest-y.

I was surfing really in my head, and really tense, I don’t know, just: Contests. Points. Make. The. Fucking. Tour. Bam, Bam, Bam. If I do this well here, or this well there, I’m making it…

And then I made it, and we’re filming the movie, it’s my first year on tour and I’m trying to get my bearings, and it just wasn’t happening—Not. Going. As. Planned.

The first contest, I show up just overwhelmed around all these competitors, freaking out, thinking I’m a kook, I don’t belong here, what am I even doing here? I’m embarrassing. Just all in my head.

Bruce Irons, Hawaii, 2017.

Photography

Max Reyes

You were melting down or feeling insecure, or what?

I was just freaking myself out, trying 150 percent, worried the other competitors are thinking, God, how’d this guy make it on Tour?

That’s what I was thinking in my head. And it’s just going: 33rd, 17th, 33rd, 17th.

I’d promised myself, after all that time trying to qualify, that once I made the Tour I wasn’t going back to the QS. It was all or nothing.

So I was just going make or break, and it was just going dog shit, the whole year.

What was it like being on tour with your brother that year, going for his second World Title, etc? Was he supportive or helpful?

I remember my brother was trying to help me out. He was, but he wasn’t.

I know he was just getting real mad that I was losing. Not in front of me, but I knew, even when I was out in the water, that he was just wigging out.

He wanted me to do well, and he wanted to help, but he was so mad at me, and he never knew how to say it. Whatever it was. And of course, he would have been right, because I was wigging myself out.

But that year, I was putting the pressure on myself. It wasn’t from the people on the beach. I wasn’t trying to impress them. I was losing it, trying to impress my fellow fucking competitors. When I should have just been out there thinking, Fuck. Them. I’m going to smoke them. But I was always trying to flare out, and feeling like a kook around these guys.

Do you think growing up around that rougher pack prepared you for that?

Yeah, that was the way you grow up there: Don’t ever get cocky. Don’t think you’re hot shit.

Like everyone says: Be humble. You can talk shit with your friends, I’d always talk shit to my brother, but I never like to talk about myself or my surfing.

Bruce Irons at the Backdoor Shootout in January.

Photography

Tony Brown

Who were those other guys who were holding you accountable?

A lot of people no one knows. It’s heavy where I grew up. No videoing. It could be real dark and violent at times. But I guess it’s like everywhere. However you act, people are going to react to that. Or you can just let your surfing do the talking. Go big, you know, and people will respond to that.

On Kauai, growing up, surfing these heavy waves, at the time, even though I was really little, I always thought of myself as being really big.

You know, I had that attitude when I was really young, especially with my brother. Always, Oh, you’re going? Well, I’m fucking going, too. No. Matter. What. That’s still ingrained in my mind.

On days when there’s no one out, and I’m looking at it, I can still hear that voice: Oh, yeah!? Oh, yeah!? I’ll show you…

Tell me about that final in France.

That’s my favorite part of [The Bruce Movie]. You know, winning The Eddie will always be the biggest thing that ever happened in my life, as far as contests or accomplishments or whatever. Or surfing in the Pipe Masters.

But that heat in France, the final with my brother, that was special.

Just being out in the water, in France, and it was so big and perfect and beautiful. Just the two of us. But my brother wasn’t going to be cool until the job was done. I was all, Isn’t this cool, brother?

And he just looked at me like, Yeah, we’ll talk about how cool this is after I drop an 8.5 on you.

We’ll talk about how cool this is when I’m on my way to another World Title.

“For me, honestly, these days it’s about not feeling shitty, just waking up feeling good.” Bruce Irons, Hawaii, 2017.

Photography

Max Reyes

After that heat, things sort of fell apart—it came down to Pipe, right?

Yeah, right after that was Mundaka, and of course, boom: 33rd. So it came down to the Pipe Masters. I had to make the finals at Pipe to requalify.

My stomach hurt the entire Triple Crown, I was just, fuck…

Then, of course, the fucking Eddie runs three days before the Pipe Masters. It was such a whirlwind. I was so stressed out. The day before the Eddie, my brother and I got in that fist fight…

The whole poker game thing?

Yeah, and I’ve got a black eye, I’m just enraged. And then I won, and that was just an other-level feeling.

But I remember we went out to dinner that night, and I was just going, Ok, that was the best thing ever. But now let’s get back to reality.

My first heat at Pipe, I had Shane Dorian, Trent Munro, and someone else gnarly. It’s like 8-foot, solid, and perfect. I think I buckled my board on my first wave. I paddle in, grab my other board and I’m running back out and my leash gets hooked on a fucking rock, and I’m just going, errrrkkkkkk—my leash is stretching out, and I’m just going, Is this it?

I was just fighting it with everything, going No. No. NO. NO. NO!

Just nope, nope, not accepting it.

But yeah, I made it to the finals. It was me, Sunny, Jamie and Kalani [Chapman].

Jesus.

Yeah. It was four, maybe five feet. And it was pretty clear that the rights were going to win the contest. So me, Sunny, and Jamie were, guaranteed, looking for the rights. But then Kalani comes and joins our little pile, and Jamie bolts over toward the lefts. And these big, swinging lefts came through, just boom, boom, boom.

Jamie got two scores, right where I would have been if I was Kalani. But Jamie didn’t want to deal with our little mosh pit.

I remember, with like 5 seconds left, the best waves of the final came through, the horn blows, and of course Sunny gets the sickest barrel, just all the way through on the first one. I got the second one; it would have been interesting to see what would have happened if that heat started 20 seconds later.

But I’m a firm believer that you get what you put out. I can remember being super down, and just negative, during a thirty-minute heat at Lowers, with Luke Egan, and one, two, maybe three waves broke the whole heat.

Lowers. Summer. Just totally flat. That never happens.

I was always doubting and negative and I swear I’ve seen the ocean bend me over. But then there are guys like Kelly or Andy, my brother is honestly the best example. He would need a score, and the wave just was not coming, but he would just Not. Give. Up. And he’d get the wave he needed, just thrash it to the beach.

You know, clinchers. To the point where it started to feel a little superstitious. It was Mojo. Will. Not accepting No. Believing it. Making it happen.

Bruce Irons, North Shore, 2017.

Photography

Max Reyes

Have you ever had that?

Um, at times. I’ve had glimpses of it. I’ve had a lot of it taken away from me by other people. Jake Paterson. Pipe Masters. Fuck. The best way you could win a contest, and the absolute worst way you could lose a contest.

That was the first year I’d surfed that contest. I had to surf through the fucking Trials. I’d surfed ten heats that day.

And here I was, I’d just graduated, just going, Wow! I’m gonna win this!

Jake needed a score, and a wave came in, I took the right and got like a 7.

I was in the whitewash and I could see my friends running down the beach, and right then I knew it wasn’t going to happen. He was going to try to grab me, and I just knew: it ain’t over until the fat lady blows her fucking horn.

I was just going, No, no, don’t do this.

And of course, five, four, there, two, one—wave comes, Jake goes, crowd goes nuts, just Rawwwwwww. Jake first. Bruce, out. That one haunted me.

But I remember at the awards, Gerry [Lopez] leaned in and whispered in my ear, Don’t worry, you got plenty of Pipe Masters ahead of you.

I’m glad I got to win that a few years later.

How long have you known Gerry?

Gerry’s the man. He’s always got just these little words for you. Keep it calm and cool, always. He was on his way out [of the North Shore] when I was coming over. He’d moved to Oregon and was surfing mountains, doing yoga, living a good, clean, healthy life. I see him every once and a while.

He shaped me a tow board I still haven’t ridden it yet. This was like eight years ago. Because you look at the board, and just know: this thing is the real deal. It’s super heavy, weighs a lot, it’s meant for 80-foot Jaws. That was 2005, 2006.

But having anything from Gerry is really special

He wrote me a letter once. I’ve got chicken skin, just thinking about it. He wrote me a letter that made me cry. It was a hard point in my life, and he took the time, and really thought about it, and he wasn’t like pointing a finger at me, he was just using these beautiful analogies to say the nicest things to me. It was a time that I really needed it.

I still have it, and every time I read it, it’s like Bruce Lee, you know? His words have this incredible meaning, the way he chooses what he says. Every time I read that letter, I get something more out of it.

He’s one of those people who, when you’re in his presence, you just feel better. Cool, calm, collected. That’s someone I look up to. For everything. Just balanced. He’s just right. And you feel that. You feel his presence. You feel his energy.

How does the North Shore feel to you today, compared to when you were coming over as groms?

Me and my brother were going over there when we were, like, ten years old. Our first sponsors were the Willis Brothers. We’d fly over and they’d pick us up at the airport, Liam and Garrett would pick us up, show us the rounds of the North Shore. Hangin out with Junior Boy Pono. That was when, if you were walking into Gerry’s house, you weren’t some goon off the beach. It was heavy. Johnny Boy. Marvin. It was nuts.

As a kid, with Liam—this was like, ’89, ’90?—it was fucking radical. The waves were so big and hollow, and the North Shore seemed so big. It didn’t seem like this little stretch. There was so much going on. It was intense.

We’d stay with them and they took us to surf Pipe, Velzyland, Rocky Point, Ala Moana, all these amazing waves for the first time. We rode for Town and Country for a bit then, stayed with Brian Surratt when we were young. Or, Dave Riddle.

But yeah, getting to surf all these waves we’d only seen in videos, you know? It was like watching TV. I’d sit and watch Pipeline all day. To see a wave that big, spitting like that, so close. I was fascinated.

And watching the guys you’d grown up looking up to, I’m sure…

Oh, [Shawn] Briley, Kelly, Derek [Ho]. Watching the Pipe Masters, even watching the Trials. It’s different now, maybe because I’m older, but maybe it’s just because it isn’t new. But it’s definitely not like it was. It was more ghetto fabulous. There wasn’t the money, so there were still people doing their shady shit to get by.

What’s it like seeing Kobe and Axel growing up in Hawaii, and here in California?

It’s so cool. That’s a generation that I’ll be front row to watch grow up. That I can’t wait to watch. Seeing them grow up. To get to experience that through them. That’s what’s happening now. And fast. I’m going to be really protective, really worried. But maybe not. Those kids are strong.

They’re being raised by a pretty amazing village.

I don’t think they realize it.

My kids are in a lot happier environment. My parents were fucking winging it. Then divorcing, single parents, for us it was, just, there’s the beach… that’s all we cared about.

Does seeing Axel and Kobe together remind you of you and your brother at that age?

Oh my god. I’m over at Lyndie’s, and Kobe’s over there, and you just hear, Whaaaaaaaaaaa. And they’re just out there on the skate ramp, laughing and crying at the same time, just battling, hitting each other with shit, almost wanting to kill each other. One of them will push the other’s buttons, and all of sudden they want to take each other’s heads off with whatever toy they have.

But they’re going to have such a tight bond. There’s eight months between them. They can battle, but they got each other’s backs.

I see them, and it just looks like my childhood playing over.

Does that feel good? I mean, considering.

Yeah, man. It does. It feels really good. I get to see that, and that’s the closest thing I’ve got to my brother. I couldn’t have asked for a better gift.

I feel like a lot of people feel that way about those kids, that they’re gifts.

They get a lot of yesses from the Uncles [laughs], so I have to be the No Guy. I have to be the guy saying, Sorry, you’re not acting like this.

And trust me, they’ve got tempers. So I gotta say, These patterns ain’t sticking. I will always be the Bad News Dad.

“[Surfing] means everything. It means happiness. You get jaded, shit goes one in your life, life goes on in your head, and you either process it and move on, or…” Parko, Bruce, and Tai Budda, North Shore, 2017.

Photography

Max Reyes

We’ve talked a little before about how it was hard, getting motivated or feeling that love for surfing for a while. But you seem genuinely, like, grom-like stoked on surfing these days. What’s surfing mean to you?

It means everything. It means happiness. You get jaded, shit goes on in your life, life goes on in your head, and you either process it and move on, or… But yeah, I got depressed for a while, man.

Which doesn’t seem like an unreasonable response.

I lost my fucking brother.

Everyone’s like, Duh, duh, duh. But I’m still living, I’m still breathing, I’m still here, grieving, I’m still going through what the fuck I’m going through… and just because people have moved on, and are done grieving, now I’m supposed to do what they want me to do?

I’m going through what I’m going through, and ain’t no one going to tell me different. Until I go through it. It’s how I’m dealing with it.

Has that been hard, with friends of you and your brother, just that always hanging overhead?

Fuck. Yeah.

It takes a good fucking person, a good friend, that regardless of what is going on, whatever anyone’s saying, they’re there for you, with that same genuine love.

Even if it’s just saying that: That they’re there for you. Just an honest, Hey, how you doing?

I tell people this all the time: I can tell a true friend when they come up to me—and say it’s been six months, eight months, whatever, and they’ve heard what shit people are saying—a friend will come up and look at you and ask you, How are you doing? He’ll look you in the eye, grab your hand, and ask: You good, man?

Yeah, I’m good.

Where someone else will walk up and shake your hand and say the same thing—Hey, how ya doing?—as he looks you up, and down, and up and down: You good? You good?

Just looking you up and down.

That’s that guy. My acquaintance.

You’ve had a lot of acquaintances in your life.

But you learn who’s who. I keep my friends around me. Not a lot. But those I trust.

Brothers fro other mothers, Dustin Barca, Nathan Fletcher, and Bruce Irons.

Photography

Max Reyes

You have dreams of your brother?

Yeah, I have dreams that are new, as if he’s still here. We’re still young, fighting. He’s getting me mad.

I wake up mad. Like, You’re still doing this to me.

And I wake up sad a lot, missing him.

I remember the night of his birthday, July 24th, I had a dream that I was at a contest, and he has his wetsuit on, a red jersey, and he’s squatting down, bouncing up and down, and I think Taj is there, and I say, Are you going to… and he just goes, Shhhhhh.

He looks at me with that look like: Don’t. Fucking. Say. Anything.

It’s weird, when I do sit down, I’ll often push out the memories of the funeral, and when I push that away it’s still hard for me to believe that he’s not here. It doesn’t compute.

I’ll watch videos of him every so often, by myself, just on YouTube, and I’ll cry and cry and cry. I did that a few weeks ago, and I need to do that. It’s a good release. I often ball it all up, and hold it in, and I’ll just let it go, get it all out, and it feels shitty and good, sad and good to be dealing with it.

That’s the path I’m on.

Has that been a rewarding process in some way?

What I’ve learned from that feeling, from that loss, is that the hardest part is missing that physical form. That spirit—I can feel it, I know he’s around. But missing that physical form.

I don’t understand it, and I probably won’t until it’s my chance to move forward into the next realm. Worrying about it doesn’t solve anything. Because what if you get there, and it’s like, the blink of an eye. And they’re right there, just, Hey! And the gap of time disappears, because time doesn’t exist.

You think about this a lot.

Yeah. I can only go off feeling and experiences. But I’m fine with death. I know that there’s something else. Because I know when this is all gone, I’ll still be conscious. Aware. Aware in the spiritual and not physical form.

This is all recent, honestly. If you’d told me the same thing six or seven years ago, I’d have said, Peace, hippie.

I started thinking about this stuff seriously after my brother died., because it takes shit happening in your life to become aware in those ways. There’s no ifs.

How do you want people to remember your brother?

You don’t want your heroes to be flawed. A lot of people I looked up to, I wish I’d never met them. You hold these people up on this fucking pedestal, and then you get to know them and you’re like, Oh, wow.

But most people didn’t fucking know my brother. Only a few people really knew my brother. If you knew my brother, you knew my brother.

A lot of people took his actions with a grain of salt, but my brother was very emotional, very passionate, very psycho, very troubled. He was a human being dealing with life and feelings.

We’re all just humans trying to work out our own life in our heads, dealing with it the best we can. I’m hoping people have a little more compassion. Don’t draw assumptions, or pass judgment. Treat others the way you want to be treated, and be ready for the outcome.

My brother loved people. He remembered everyone’s name. I couldn’t believe it. He remembered everyone’s fucking name. And if you were genuine, and my brother liked you, he liked you. We were raised to think of ourselves the same as anyone else. If he felt good intentions from you, if he got that vibe from you, he was down with anyone. That was one of his beautiful traits. That was my brother.

Bruce and Cory Lopez, at the “Andy Irons: Kissed By God” premiere in Los Angeles.

Photography

Victoria Moura

Last night, Bruce politely made his rounds, forgivably rattled-looking, being warmly and thoroughly embraced by old friends and receiving kind consolations from acquaintances.

I’d let Bruce know we were running this interview, which I’d done a few weeks after filming for the documentary had wrapped, and for which Bruce was more than generous with his time. As Bruce made one final dash through the crowd, he stopped and looked me in the eye, smiled, and gave me a hug without so much as a word, as we both knew there was nothing left to say.

I hope you all take the time to watch “Andy Irons: Kissed By God,” whether at one of the 500 theaters screening it later this month, or at the two remaining premieres in New York and Hawaii.

It’ll break your fucking heart.

Sincerely,

AG

Comments

Comments are a Stab Premium feature. Gotta join to talk shop.

Already a member? Sign In

Want to join? Sign Up