Long Read: An Angel At My Table

From Stab Issue 15, October 2006: Chris Davidson has one more shot at the big time before professional oblivion.

[Note: This article — written by Fred Pawle, with portraits by Mick Bruzzese — originally appeared in Stab Issue 15. It was published in October of 2006. Davo requalified for the WCT in 2009 and competed in 2010 and 2011 while sponsored by Lost. His best result was a 3rd place finish in Portugal in 2010.]

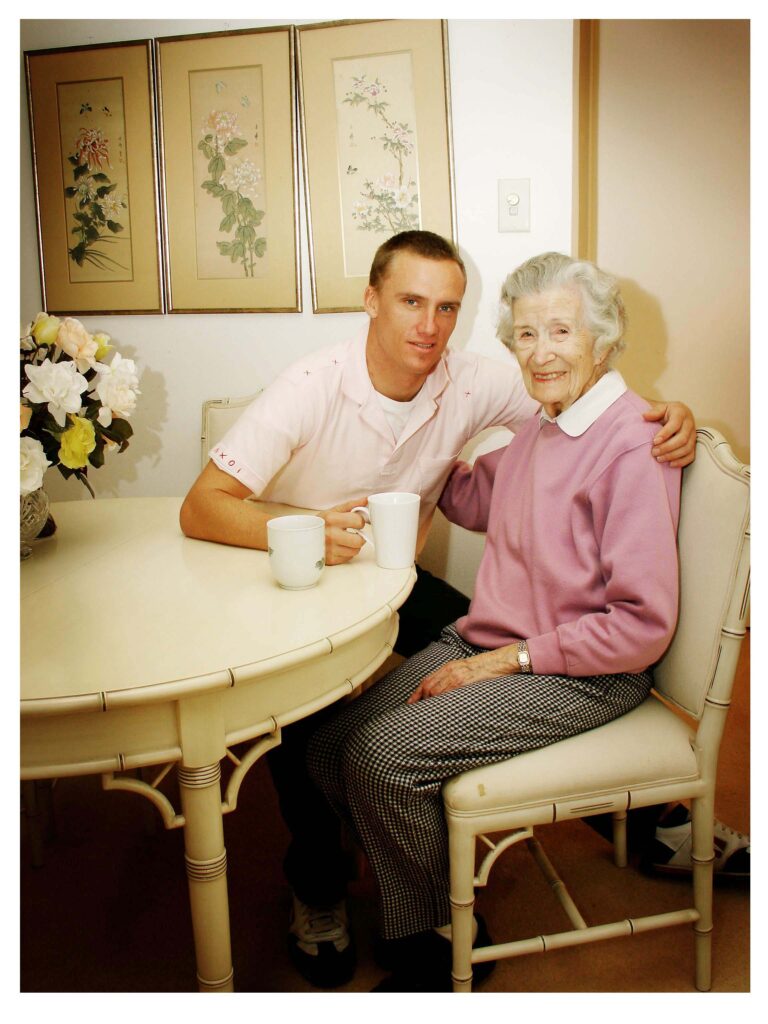

There’s a new woman in Chris Davidson’s life. And she’s 87. They share a two-bedroom flat in a 1970’s tan-brick block, inhabited mostly by retirees, on busy Pittwater Road, the main drag between Collaroy and Narrabeen. There are Chinese prints on the wall, biographies of famous Australians in the bookcase, a sideboard crammed with happy family snaps and an old vase on the dining table with fresh roses in it. It’s hardly the kind of place you’d expect Davo, the erratic star of the ‘90s, to be happy, but he is. Well, at least relatively. I’ve just spent the day with him. Surfing Northie and raking through the misfortunes of the recent past over a beer at the newport arms. When we return to the apartment in the late afternoon to rendezvous with photographer Mick Bruzzese, he’s more than happy to pose with his flatmate as if they’re a couple of young lovers.

“This is my new life!” he grins.

The flatmate is Angel Ison, Davo’s grandmother’s sister, his great aunt. Davo moved in with her late last year. “Its like rehab for me,” says Davo. “I moved in to be by myself so I wouldn’t be doing drugs and being with my friends. I wasn’t happy with who I was and the way I was going about things, the way I was treating people and the way I was treating myself.” Just how badly he was treating himself, and others, was what I wanted to know when I rang Angel’s crib back in July. I’d heard the rumours about Davo squandering all his money and being a little lost. He wasn’t home, but Angel was hip to talk about the boy she took in just before Christmas last year because she thought the whole world — including, to some extent, his own family — had abandoned him.

“They [the family] said to me, ‘You’ll be sorry, you shouldn’t have Chris staying with you’,” Angel said. “The answer to that, for now and forever, is I can’t do that. Chris will always be welcome because, even though we’ve had a few headaches, he’s brought me a lot of pleasure. He always treats me with the greatest respect, and I really do think that’s what he’s like at heart.” She wouldn’t be the last person to tell me that Davo, despite his occasional thieving, deceitful and violent ways, is essentially a good bloke.

“A lot of Chris’s manner is a cover, a self-defence. I get wound up about Chris. I find that when I talk to people, they do see that there are two sides to the coin. I just hope I’m doing it right [by looking after him]. You can only do your best. I’m hoping that I can just get him straightened out a bit before I fall off the twig.

Angel goes on to elaborate about that “other side of the coin” and divulges something about Davo that you probably didn’t know: his dad Ted was a Vietnam vet. Raising a young family (Carlie was born in 1973, and Davo came along in 1976) while trying to shake the horrors of what he’d seen on the frontline would have been hard enough, but when one of your kids is self-centred, precocious, and somehow hardwired to defy all forms of discipline, things are only going to get tougher. Ted was almost preordained to hit the bottle — his own mum (Davo’s grandmother) was an alcoholic — to the point that she was incapable of raising her son. Ted was pretty much raised by his aunty Angel and his grandmother.

“Ted was gorgeous,” Angel says. “He had enough of the devil in him to be interesting. But he had a really bad time when he came back from Vietnam. They all did. Ted followed his mother’s pattern and turned to alcohol. It was 10 years before he got out of it. We had an excellent doctor who told Ted, ‘You’re going to be dried out — you’ve got too much to lose. He had his own home and these two little children. “His wife was just wonderful. Mum and I were there to support, but you’ve got to give Sue [Davo’s mum] full marks. She was not going to let her family break up. Ted went in to a rehab place. He was only there for six weeks and he’s never had a drink since.”

Eventually, I get her talking about Chris’s demons. Angel likens Davo’s creativity and self-destructiveness to his wretched grandmother. “It was always going to be tricky for Chris. I could see the pattern of my sister. They both had a talent. My sister was a bit overbearing too. And she had a wonderful musical talent. She played the violin beautifully. Davo was in a bad way when he came to Angel last year. He’d just been dropped by Globe, he’d bailed early from the North Shore because of trouble with the locals, he had just smashed up his expensive V8 Holden, he wasn’t seeing much of his seven-year-old son Dakoa, he was broke, and heartbroken about blowing it with his fiancée Amber, who’d dumped him in April, and he was sick of trying to deal with all the desperation and unhappiness.

“He was pretty introverted,” Angel says. “He’d sleep in, and meander out to the kitchen in the mornings. I could tell when he was going to have a bad day. He’d get angry about somebody and raise his voice.

“I’d say, ‘Chris, I’ve got no problem with what you say — get it off your chest. But just bring your voice down a couple of decibels.’ [Now] he never raises his voice. And the neighbours here think he’s gorgeous. He never has loud music. And do you know, he never brings drinks in here. He’s never come here under the weather.

Davo’s sister Carlie isn’t convinced. “Angel is an awesome, wonderful lady, but Chris is not [at her place] all the time. And she can’t hear very well, or see very well, and she’s probably turned a blind eye. “I hope he’s off drugs, I really do. But, you know, I’ll believe it when I see it — can I say that? And I mean off everything. Not just the heavy stuff. Until he’s off pot, I don’t see that there’ll be many changes. Pot is the base of his problems. Until he gets off it, I don’t care if he’s off the coke and whatever other things. Until he’s off everything 100 per cent I don’t think he’ll get on the right track. He can’t control it enough. Some people can, and some people can’t.”

Carlie’s no prude. She’s seen a bit of the party scene herself — “just enough to know what goes on round here.” But the gloss disappears when you see the damage up close.

Carlie’s sceptical about Davo’s claims that he’s cleaning up his life. Last year, he was keeping some of his stuff at her place, across the road from North Narrabeen. She was happy for him to come and go, keep his boards out the back, even tuck into the fridge if he was hungry. But he became “angry and out of control,” even picking a blue with her husband on the front lawn one day. She threw all his stuff out and changed the locks. “I’ve got children, I don’t need someone like that in my house,” she says.

Even now, not much has changed: “It was my birthday a couple of weeks ago, she says, “and he rang a week later. He said, ‘Happy birthday, um, and by the way can I borrow $50? I’ll give it back to you tomorrow.’ I said if you don’t have money today you won’t have it tomorrow. I said I have to work to get that money. Do you work to get yourself out of financial difficulties? No response. Then he said, ‘My phone’s beeping, I better go.’ I haven’t heard from him since.”

Davo’s bad run started in December 2002. He had just finished 7th on the WQS, and was back on the WCT for 2003. He was still with Rip Curl. He should have been loving life. Instead, he got in a blue in a pub in Manly. Luckily, he got off with a suspended sentence. Luckier still, news of it never reached the ASP. When I ring ASP executive director Rabbit Bartholomew and ask how the sport felt, in 2003, about having someone recently convicted of a violent offence in the WCT, he says he never even knew about it.

“For some reason, news never reached us,” Rab says with obvious surprise. “It’s hypothetical now, but he would have had to face a disciplinary committee if he’d brought the sport into disrepute. But there was no publicity, even in the mainstream media. That’s very lucky.”

That’s about where Davo’s luck ran out, though. Rip Curl, his sponsor since 1989, dropped him. Or, as Davo puts it: “My contract said that if I get an assault charge, or anything that makes [Rip Curl] look bad, then they’d have to get rid of me.” Globe quickly snapped him up, but the bad run continued. In an act of cosmic retribution, this time it was Davo on the receiving end of the jagged glass. In April 2004, at the Salomon Masters at Margaret River, he had just won his heat in the round of 32, and was running back into the competitors area, when he trod on a broken bottle in the sand, and severed a tendon. With one unlucky step, he had suddenly sentenced himself to four crucial months on the couch, missing WCT contests at Bells, Fiji and Tahiti.

“That injury affected him in a massive way,” says Amber, who had by then been going out with him for three years and had started wearing his engagement ring. “He’d finally got himself a new sponsor. We were really happy, he was going really well at Margaret River, I was about to meet him at Bells… and it just all fell apart.”

Davo limped home to Sydney and spent four months on the couch, in pain, with his foot in a plastic cast. The inactivity drove him mad, says Amber. “Even though he doesn’t work, he’s always out and about. He’d just bought a new car and couldn’t drive it. He was really depressed. And whatever [drugs] he was taking, it was purely to keep himself occupied. It was really not good. But, being Chris, instead of just dealing with it, he had to take it to another level. When something goes wrong with Chris, everything goes wrong. He can’t see anything and he throws it all away.”

Davo started getting paranoid, especially about Amber’s movements. “I’d say, ‘It’s cool babe, I love you, don’t worry.’ But he was stressing because he was doing nothing. That was when he started getting needy and that’s where all our problems stemmed from.”

He got back on his feet and took Amber to the six-star event in Lacanau in August, 2004, where he came second to Bede Durbidge. You can imagine his delight. True to the hype that had surrounded him since childhood, he had bounced back with a freakin’ vengeance. He and Amber hit the town. Being Davo, he was on a mission, although Amber says that all he consumed that night was alcohol.

Then, another disaster. Towards the end of the night, Davo, confused by the narrow streets of the French coastal town, drove the wrong way up a one-way street and straight into an oncoming car.

“He had never drunk champagne before and he was drinking a bit of it,” says Amber. “And when you don’t drink it, you can get pretty drunk. He was drunker than he thought.”

Amber wound up in hospital with a badly injured back and Davo was overcome with remorse. “He was feeling really guilty. He’d come and visit me in hospital and I’d have to send him home because he was crying. I wanted to feel better and he was just too emotional. It was too much.”

Davo followed this up four months later with arguably the dumbest of all the dumb things he’s ever done: he bailed from the Nova Schin WCT event in Brazil in November, saying he had to stay home and care for Amber, who was still recovering from the back injury. His WCT rating slipped, as had his rating on the WQS, despite the huge result at Lacanau. Davo was facing elimination from the WCT for the third time in his career.

With typical chutzpah, Davo placed all his faith in getting an injury wildcard back into the WCT and turned up at the meeting of the World Professional Surfers at Waimea Falls in December fairly confident that he’d sneak back in for 2005. He had a good case: the four-month lay-off was due to an injury incurred at an ASP event. He’d at least given the QS a go. And, of course, he was still ripping. Nobody could argue that he didn’t belong in the CT.

He should have been a shoo-in but he blew it with his attitude, says Jake Paterson, who organised the WPS meeting where the injured supplicants put their cases.

“It was really close,” says Jake. “Davo started talking about how he had a car crash with his missus and he couldn’t go to Brazil because he had to stay with her. But all the boys knew he’d been drinking the night of the crash. He had some sort of doctor’s certificate that basically said it the reason [for not going to Brazil] was more mental than anything else. It was in his head that he didn’t want to go, some sort of anxiety attack or something. He should have run with the story about the cut foot instead of carrying on about how he couldn’t go to contests because he had to look after his girlfriend. A few of the boys didn’t think that was part of his case and didn’t have any sympathy for him. He didn’t put his case across as well as he could have and Beschen [who got the wildcard] milked it for all it was worth, shedding a few tears. “Davo has had a run-in with pretty much everyone on tour, which didn’t help his case either. He just tells it the way it is, which I admire. He speaks his mind, he doesn’t backstab people, he tells ’em straight to their face. If he reckons you got through a heat cheaply, he’s gonna tell you. I reckon that’s pretty cool. It’s got nothing to do with the boys not wanting him to be on the tour. His ability speaks for itself. He’s an amazing surfer. It was that he didn’t even have to go for the wildcard. If he’d pulled his finger out and gone to the contests that he had to go to, he would have requalified anyway. All he had to do was turn up at Brazil, and he would have qualified.”

Davo’s own account is similar, albeit laden with vitriol he still can’t shake a year and a half later. “They promised me the last wildcard,” he says. “I put down a book of papers, x-rays of what happened, this, that, everything. They said I should have gone to Brazil, and I’m like, ‘What, and leave my fiancée with a broken back? She can’t do anything. She can’t even walk down the road to the shops. You guys should be cutting me some slack.’ I injured myself inside the competition area of an ASP event. All fucken Beschen did was twinge a knee ligament at the first event of the year. He didn’t even do the QS. He gave them one page [of documentation] and cried in front of them and got it.”

The next 12 months were spent in a spin. He was sponsorless, and not competing full-time for the first time since he’d burst onto the scene 12 years earlier. He started defaulting on mortgage repayments, Amber left him, and, according to reports about his behaviour and appearance, the Narrabeen “epidemic” was getting the better of him. Davo’s next disaster was to smash his HSV Club, which he’d bought from V8 Supercar driver Jason Bright, at the tag team surf comp at Curl Curl in December last year. He had been granted rare access to his son Dakoa (who had long since moved with his mum to Maroubra) that day and had the kid in the car while he was clowning around, showing off in the car park. He lost control doing a burnout, and slammed into a parked car. The damage was extensive. Davo himself is a bit circumspect about it all.

“I’ve done a lot of stupid things and it’s been because I haven’t known how to channel my anger and depression. Just not thinking. You should think before you act and I never did. I’d be like, whatever. I never used to give a fuck. But now I look differently on things. When I look back, I can’t believe the things I used to do. What was I doing?”

He reckons he could get the car back from the insurance company if he could raise $7000. Meanwhile, he’s trying to sell his little two-bedroom apartment in Newport and hopes to use what’s left, after the bank’s taken most of it, to buy some land up near the Gold Coast. Davo’s at the stage where he’s realised he’s fucked up in a big way but still can’t work out why. He blew it with Amber because he cheated on her, and admits to being “dragged into a hole” by the drug” epidemic” around Narrabeen. He’s always been angry because his dad was “a touch violent” towards him as a kid. He was “shattered” when Dakoa was taken away from him. He was given too much money as a kid and his ego got out of control.

But he backs this with only vague convictions about being a nicer bloke these days. At the risk of blurring the line between profiling and counselling, he’s still got a lot of growing up to do. Davo’s obsessed with the big picture but can’t be bothered with the details. And he’s vague, at best, about accepting responsibility for his own actions. “Chris is a bit delusional, he lives in a fantasy world,” says Carlie. “I’ve heard this story [about dad being violent] a few times. He’s said it to a couple of girlfriends and I don’t believe it. He uses it as an excuse for his behaviour, to make people feel sorry for him. But dad was never unreasonable. Chris got a smack on the bum occasionally and the belt was brought out as a threat. Just like every parent. That’s all dad ever did with Chris, just to keep Chris in line. But Chris, right from the start, didn’t follow discipline. He’d be told to get out of the water at 5:00 pm and mum would still be waiting on the beach at 8:30 pm in pitch dark. You can imagine how upset dad is about Chris. He’s completely heartbroken and so is mum. She did everything for Chris.”

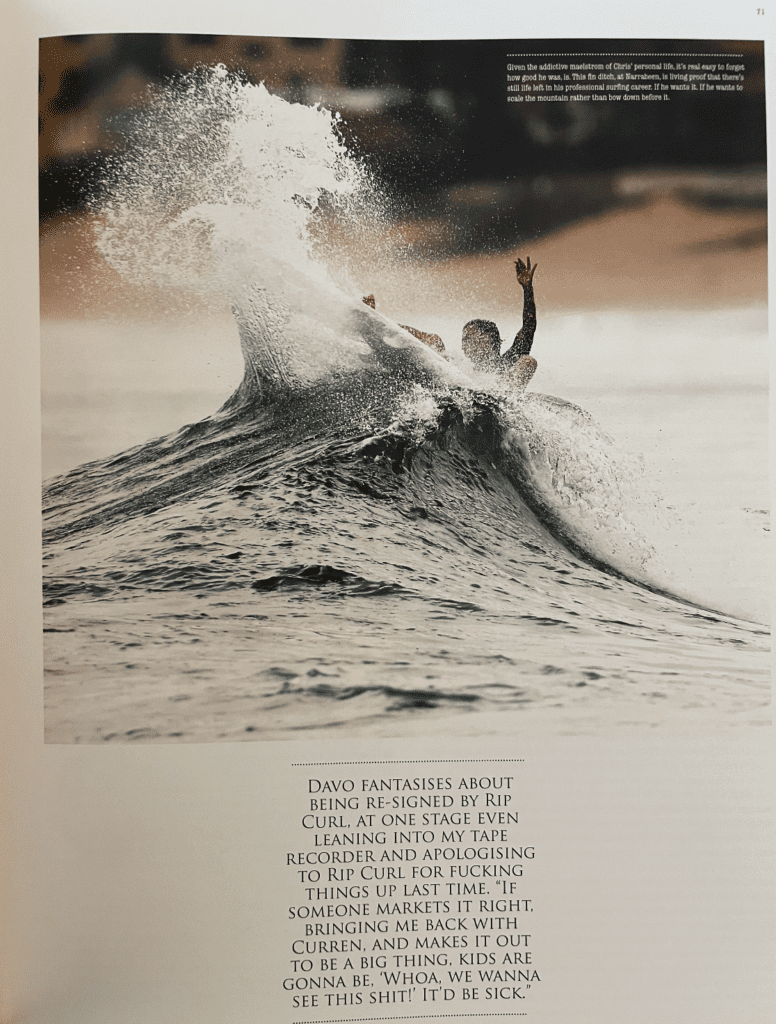

Family problems aside, Davo’s biggest challenge is to bust back into pro surfing. He might have seen a lot of drama in his life but the kid’s still only 29. He fantasies about being re-signed by Rip Curl, mentioning it a few times during our chat at the Newport Arms, at one stage even leaning into my tape recorder and apologising to Rip Curl for fucking things up last time.

“My dream is to be back with them. That would be the best way to end a career… maybe doing some Searching with Tom Curren, maybe doing some Lost Files, depends what they’d want me to do. I know it’s a privileged position but it used to work so well and it would be silly for Rip Curl not to do something like this. At the moment all the companies have gone really quiet with movies. Rip Curl just have to make it a big deal. It’s the marketers that can make it. If someone markets it right, bringing me back with Curren, and makes it out to be a big thing, kids are gonna be, ‘Whoa, we wanna see this shit!’ It’d be sick. All the old boys — Curren’s in it, and my age group. Fanning’d come along with us, and Hedgey. I think it’d be incredible.”

Feasible? “It’s a fanciful idea,” says Gary Dunne, Rip Curl’s international team manager. “I’d never say never, but it’s so unlikely. We haven’t sponsored him for nearly four years. Rip Curl’s moved on and Chris probably needs to as well.”

On the way from the pub back to Angel’s crib, I ask Davo if he could requalify in a year. “Yeah, definitely,” he says. But you need 30K to do it and you’ve got no sponsors. Would you use your own money? “I haven’t got any money.” But you said there’d be some left after the sale of the Newport crib. “Yeah, but I want to try and buy a place [up on the Gold Coast]. If that’s the case, I want to start doing something different, whether it’s competing or whether it’s in the surf industry, or doing some other job but my heart lies in surfing. That’s where I want to be.” Somewhere in that reply is the hint that deep down Davo is struggling with the prospect of retiring — voluntarily or otherwise — from professional surfing.

If he does, he’s in for another big fall, says Rabbit. “Anyone who retires has to come out of the bubble,” he says.” You come out of this fantasy world and for every single one of them there’s a transition. Most guys these days have management that looks after their money and invests it for them. It’s a lot easier to retire from a sport with a couple of mill in the bank. Some never really have to come out of the bubble. If you’ve got three to five mill in the bank, you might never have to come out of the bubble. You might never have to face the reality that 99.9% of human beings face, which is to get a job.”

But Davo’s dreaming if he’s even vaguely thinking of retiring, says Rab. “He’s still a young man with all his physical facilities intact, there’s nothing wrong with his surfing ability,” he says. “If Mark Occhilupo can be on the tour at 40, I can’t understand why Davo is suddenly facing retirement. In my opinion, he’s just not prepared to do the work to get himself back there. If he’s looking at retirement, then under his own volition he’s quitting. He’s got a Mount Everest in front of him. Some people like the challenge. Others will look at it and go, ‘It’s too high, I can’t do that.’ You can’t look behind people and see what makes them tick, but I would think that if he’s looking at retirement he’s really underdone himself. He’s had a bit of bad luck. I like Davo. And I feel bad about him — not bad that we haven’t done enough, I just feel bad to see him end up like that. He had so much promise. I reckon he should knuckle down, train for the rest of this year, and have another go next year, and see what he can make of himself. He’s got a long time for the rest of his life to do nothing. Why not put that off for a year?”

Climb Everest? He’ll never do it, says Wayne Munro, Davo’s manager from 1999 to 2002. “The guy rips, but these days it’s not just having the talent, you’ve got to have the head,” he says. “There are guys who have made it who haven’t got the talent. But they’ve got the head for it. That’s how it’s

changed.”

Not only that, but Davo struggles with man-on-man heats. His competition record shows that he can breeze through the four-man heats of the WQS but when he gets to man-on-man in the WCT he crumbles. “I used to get phone calls at 3 am, stuff like that. It was about his career. When he wasn’t performing, he’d worry. He doesn’t like man-on-man. That was one of his biggest problems. Davo’s got a heart of gold but he never had a lot of confidence in himself. That’s why he hit the drugs a bit. He never thought he was as good as he was. So when it came to the man-on-man format he was always going to struggle. But with a four-man heat it’s easy. I used to tell him how good he was and how much potential he had, and deep down I don’t think he believed in himself enough. He’d just go, ‘Yeah yeah yeah, well how come I don’t fuckin do this and how come I fuckin don’t do that?’ That was his whole attitude. You’d hit him with a positive and he’d hit you back with a negative. It’s really hard to get someone positive when they hit you with negatives all the time.”

For each of the people I’ve quoted in this story, there’s another couple I also spoke to with similar stories and attitudes towards Davo. But check this: all but one of them hopes the kid can still pull himself together. Even Carlie, who has probably put up with more crazy behaviour than anyone, says, “I feel sorry for him — it’s sad because he’s got a wonderful heart underneath all the crap and the lies and the deception that sit on the surface. He was a kid who was given too much money and not taught anything.”

Were you encouraged to be a rebel as a kid, I ask him. “I think it’s the path I took, sort of, he says. “Rip Curl were sort of liking it. It was the path I took and the life I was living. But now I’ve stepped totally away from that sort of image. I don’t want anything to do with that bad-boy image. I just want to be known as Davo, good surfer, nice guy. I don’t want this bad boy hype. It’s just crap, really. I got my [selfish] attitude when I was young, getting given so much. But now I look at things differently: you’re not better than anyone else. You might be a millionaire but you’re not better than the guy next to you, no matter what. It could all be gone tomorrow. That’s what’s happened to me. I’m still fighting for what I believe in and that is that I’m a good surfer. Within a couple of weeks of this interview, he’s up on the Gold Coast and ripping the Superbank like a crazy teenager, doing five run-arounds a day. If the horror stories about his descent into meth are true, he’s kicked it and got his fitness back. Whether he can make it pay is the big question.

Back in Collaroy, the shoot’s over, I’ve said goodbye to Angel, and Davo walks me to my car. We linger a while and somehow the cautionary tale of another overpaid youngster comes up. Davo wants me to know that he ain’t no repeat. “I’m not like Nicky Wood,” he says.

Comments

Comments are a Stab Premium feature. Gotta join to talk shop.

Already a member? Sign In

Want to join? Sign Up