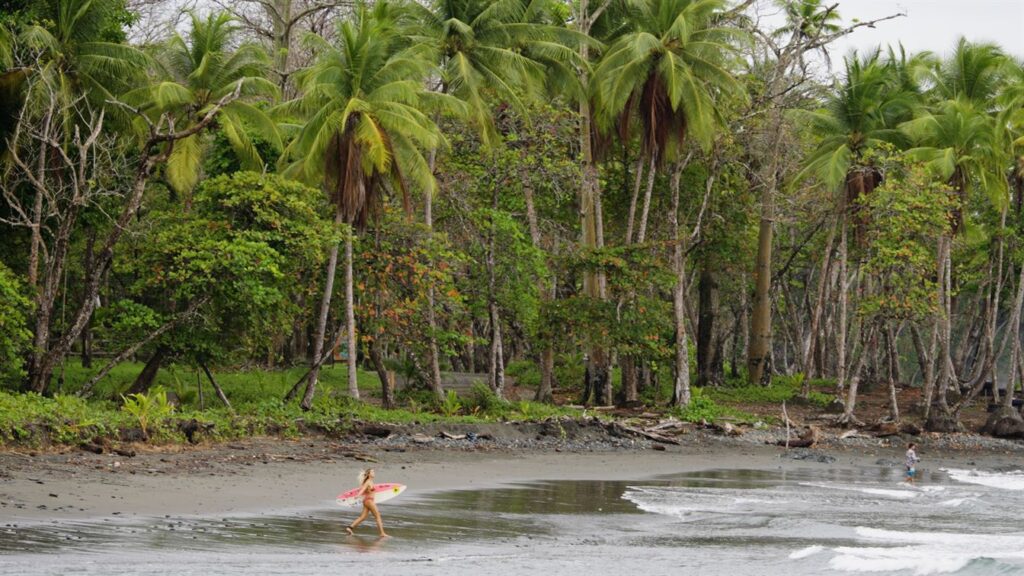

Why Is One Of The World’s Longest Lefts Being Bulldozed?

Pavones residents displaced as excavators move in.

Flick through the pages and it reads like a familiar story. A wave found, cherished for a time, then leaked to the world. A jungle cleared, a brochure written by stage-two settlers.

First, wooden huts for charm, then turned concrete for permanence. A few roads to connect the ambition. A bar, a pool with a view, a yoga shala and a tennis court. Suddenly, the locals can’t afford lunch, let alone smoothies named after chakras. The dream, once public, is now monetised, fenced off, and booked out six months in advance.

But that’s not what’s happening in Pavones.

Read slower, and you’ll find that what’s unfolding here isn’t a clichéd tale of paradise lost. It’s much stranger, and perhaps more heinous and heartbreaking, than that.

The story of Pavones begins not unlike the story of G-Land. A long, jungle-wrapped left, spotted from a plane window by a Western man who assumed, correctly or not, that he was the first to see it. He goes in for a closer look, sets up camp, and stays.

Both discoveries would become legendary. Both men would become landlords of their respective dreams. And both, in time, would be taken out by the government on drug charges.

Unlike Boyum, it seems Dan Foley didn’t arrive looking to hustle paradise. At least not at this stage of his life. By most accounts, he genuinely intended to settle, live quietly, surf a lot, and offer up space on the land he bought to anyone who needed a place to sleep.

“He amassed 15,000 acres of beachfront land,” says Dan Harmon, the documentarian in the video above. “He became an iconic figure in the area. His money flowed into the town, funding roads, clinics, and cattle ranches. Locals affectionately called him the ‘King of Pavones.’”

Foley clung to the dream for almost 20 years before being clamped on federal drug charges and shipped back to the U.S. in cuffs. That was the end of the fairy tale.

With Foley out of the picture, the land became open to interpretation. Locals began squatting, unsure if he’d ever return. Eventually, they stopped waiting, and homes and businesses were built on his land.

“Pavones became a strange limbo land,” says Dan. “No one really knew who owned what. The town fell into a legal mess of overlapping claims and shady land sales.”

Adding to the confusion was a particular Costa Rican law: if you live on and use a piece of rural land peacefully, openly, and continuously for 10 years, without being removed, you can gain legal rights to it. Pavones, being rural, applied.

So, those who’d popped a squat had, with years to spare, earned legal rights to the land. Pavones carried on as it had — half-legal, half-magical, mostly undisturbed. Until May this year, when bulldozers arrived without warning, backed by riot police, and began methodically flattening the town.

Family homes, local businesses, fisherman sheds, you fucking name it. Rumour has it, all in the name of a full-stick luxury beachfront development. Sixty high-end condos, wedged along the Pavones shoreline like cock-eyed affluence. The wave, potentially, set to become privatised.

How do you pull off something like that? Well, you don’t need consent. You just need a loophole.

“These demolitions come under Costa Rica’s 1977 zoning law,” explains Dan. “It bans unpermitted permanent structures from being built whiting 200 metres of the high tide line, which is where many of the towns most iconic businesses are situated.”

But the law also states that evictions require a formal legal process. Which means that unauthorised demolitions — even of technically illegal structures — are, themselves, illegal. Outrage, as you’d expect, followed swiftly.

With many long-term residents now homeless and unemployed, local organisations are challenging the legality of the demolitions. They’ve accused the authorities of picking and choosing when to follow the book and, notably, who it applies to. Several foreign-owned hotels, some within the same 200-metre zone, have remained untouched. The bulldozers, it seems, had a clear preference for local businesses and family homes.

“Legal action has started,” says Dan. “There’s been a constitutional appeal filed against the Ministry of Public Security and the Municipality of Golfito for alleged irregularities in the eviction process.

“The timing of these evictions is also very suspicious,” he adds. “The rumours about the condos started almost immediately after the clearings began.”

Officials, of course, have denied any coordination with developers. But the timing, coincidental or not, follows a familiar pattern. Development projects, from Costa Rica to California, tend to have a way of side-stepping ethics, heritage, and environmental law when money’s in the room.

The luxury project is said to include a marina, expanded road access, and, of course, sixty beachfront condominiums. The government insists the development is not only legal, but essential for the region’s economic growth. What’s less publicised is the alleged bypassing of required legal processes, not to mention the absence of any environmental impact assessments.

But out of the rubble, something inconvenient has returned: the people. Fishermen, farmers, and families who go back to the Foley days have started rebuilding. Temporary structures, for now. When the authorities show up, they don’t move. They’re reclaiming what they see as ancestral land, and doing what they can to keep their homes.

It’s a David vs Goliath situation, or more accurately, community vs capital. Goliath, in this case, is wearing a hard hat and a development grant.

If you’ve figured out which side of the fence you’re on, you can act accordingly here.

Comments

Comments are a Stab Premium feature. Gotta join to talk shop.

Already a member? Sign In

Want to join? Sign Up