Trash Floods Bali’s Beaches Again

The wet season has blown the lid on Bali’s worst kept secret, again.

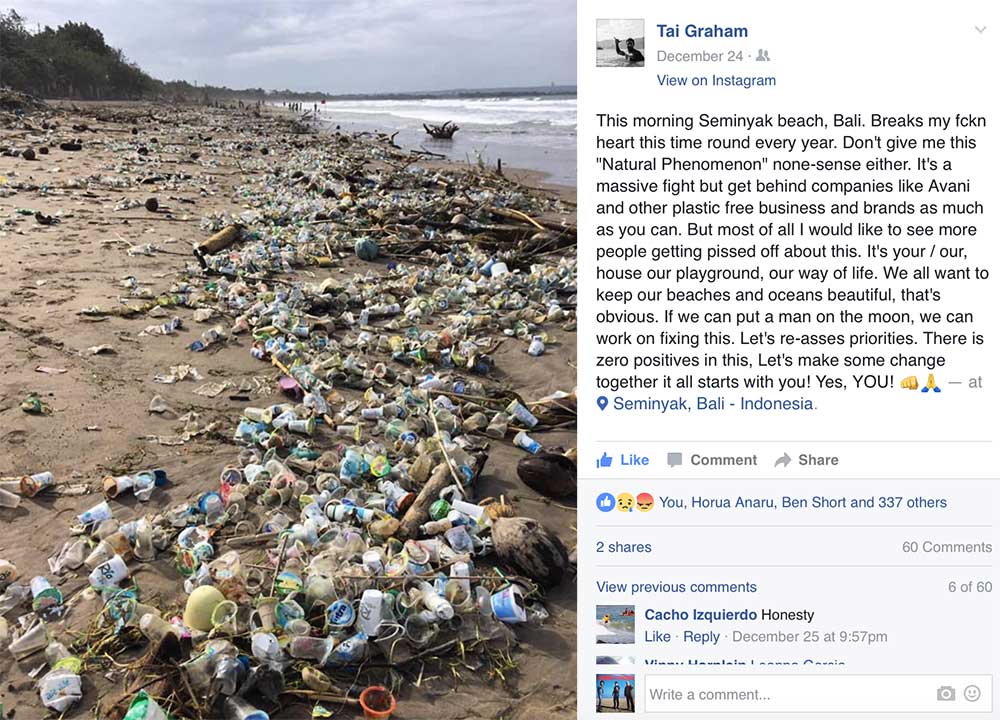

It’s that time of year again when the monsoons arrive, the tourists depart, and Bali’s pristine beaches turn into a hellish goop of trash and disease. A photo of Seminyak, on Bali’s west coast, shared by longtime Bali expat and pro surfer, Tai ‘Buddha’ Graham, showcased the surreal and devastating scene. All kinds of trash – from an array of plastics to needles and medical waste – can be found all along Bali’s coast, from Uluwatu to Canggu and beyond.

With the arrival of the wet season, Bali’s tropical trade winds switch to onshore delivering tonnes of waste to the coastline and exposing the island’s worst kept secret.

When western surfers first arrived on the island in the early seventies the Balinese were still using organic materials that left no waste behind. But as the Western influence poured in, the island of the gods, along with the rest of the Indonesian archipelago, became inundated with trash.

“Over the last 20-30 years of course (it has gotten worse), but I’d say over the last 10-15 years its been growing slowly each year,” explains Tim Ross from Project Clean Uluwatu, an organisation focused on “liquid wastes generated by visitors to Uluwatu, through a bio septic and waste water garden system.”

Lee Wilson enjoys the fruits of Bali’s east coast. Photo: Scotty Hammonds

At the heart of the problem is a lack of education and investment in waste disposal methods and infrastructure. In southern Bali, home to the vast majority of tourist activity and development, the quantity of solid waste produced each day exceeds 240 tonnes. Much of it ends up in poorly administered, sometimes illegal, landfills or the islands vital river systems, which then release it into the ocean. Elsewhere, locals are famous for burning trash outside their homes despite the myriad of toxins and health risks created – among them increased cancer rates (generally lung, throat, prostate), mutations in the development of the male reproductive system, immune system malfunctions, reproductive/birth defects, kidney disease, and many respiratory illnesses such as bronchitis.

Damo Hobgood, the Bukit, and a scenario worthy of attention.

It’s led many in the surfing community to voice their disapproval, among them Kelly Slater, who said the trash problem threatens the very future of surfing in the islands.

“If Bali doesn’t #dosomething serious about this pollution it’ll be impossible to surf here in a few years. Worst I’ve ever seen,” he tweeted back in 2012. Kelly later donated a signed surfboard to be auctioned for the cause.

“I think this issue is much bigger than just the surf community, obviously there’s some infrastructure that needs to be put in place in Bali and this part of the world to do something with the waste rather than put it in the ocean. If you walk down the beach without shoes you need to pay attention, as there are needles, random trash, all sorts of debris and medical waste. Yeah it’s a problem for the people who travel here and love coming to this place, but it’s more of a problem for the people who live here, it’s a really important issue,” he said.

Luke Davis scoops under a lip that should be a much lighter shade of green. Photo: Damea Dorsey

Several NGOs and local community groups have sprung up in response to Bali’s trash problem, including R.O.L.E, Project Clean Uluwatu, and Bali Beach Cleaners. But they are fighting a losing battle.

“The most realistic way, sadly, is that change only seems to happen when there’s money to be made or money to be lost,” explains Tai Graham, who has lived on the island since he was a child.

“When the big companies take a hit with the loss of tourism dollars, or better still if someone can turn that trash into cash – we’ll have he cleanest beaches around. But it all starts on the schools and at home. The true local Indonesian people need to take the sense of ownership and get pissed off when they see someone throwing trash away. Like in Oz or the US, people get angry when they see it.

“Through education of course but hitting them in the pocket will be where it sends the message hardest. A fisherman no longer making his normal haul affects him and his family, or a guy renting umbrellas and deck chairs on the beach. Indo is so community based, once the key voices get the right tools to spread the word – I believe it will change,” he says.

Tai, and the very reason he spends so much time in (and has such great concern for) Bali. Photo: Jason Childs

Comments

Comments are a Stab Premium feature. Gotta join to talk shop.

Already a member? Sign In

Want to join? Sign Up