Will Surfers Be The Harbingers Of The Microbial Apocalypse?

According to scientists, there’s a chance.

What’s one of surfing’s most imperative admonitions? Don’t bet against Kelly Slater at Cloudbreak? Never rely on a hurricane swell? Don’t be a hero? All wrong! Think with less sarcasm weighted in certitude!

The answer: Don’t surf 72 hours after it rains. Next to the conditions at your local break being a disappointment veiled in uncertainty on any offshore day and never wearing a short arm, short leg wetsuit, ever, it’s one of surfing’s golden rules. Why? Because, you’ll get sick from runoff, which carries bacteria, land-based toxins and general grime into the sea. Nasty stuff, literally.

Follow that procedure and you’ll feel healthy as Laird Hamilton does every day after breakfast. Or, so we thought.

Some fresh research conducted by the University of California, San Diego’s (UCSD) Center for Microbiome Innovation found that surfers may be more susceptible to exposure to dangerous antibiotic-resistant organisms unique to the ocean itself.

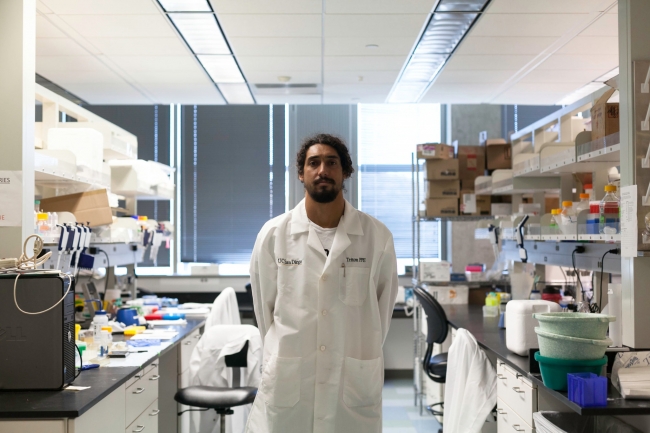

Cliff Kapono, a researcher, and surfer, working with the UCSD Center for Microbiome Innovation. Photo courtesy of The New York Times.

Background: Many antibiotics used today derive from chemicals produced by microbes to defend themselves or to attack other microorganisms. No surprise, then, that strains of competing bacteria have evolved the genetic means to shrug off these chemicals.

And while drug resistance comes about because of antibiotic overuse, the genes responsible for creating resistance are widely circulated through nature and have been evolving in microbes for eons. Because the ocean acts as a reservoir for these genes, among others, that means our amphibious demographic has a higher chance of exposure.

For the uninitiated, these organisms are bad news. Like, the potential end of life as we know it bad. Imagine the cinematic conclusion of War Of The Worlds, but we’re the aliens that are mass annihilated by nature’s most effective genocidal agent: Microbial infection.

Obviously, this scenario is on the drastic end of the probability spectrum. But imagined as a coin flip; it’d be a land on heads (which would happen substantially, and you’ll probably ask yourself if it’s a loaded coin), life goes on; land on tails (the one odd time), and it’s Black Death: Episode II — Attack Of The Immedicable Pathogens unfolding in real time.

So, now that you know what we’re dealing with, here’s why you might need to worry. Because bacteria picks up and passes on genetic information across species, researchers suspect the risks of acquiring resistant genes are higher in places that facilitate direct transfer of body-inhibiting microbes in this nature. By universal estimates, surfers swallow about five and three-quarters ounces of potentially affected saltwater per session. See the connection?

Twenty-nine-year-old biochemist, native Hawaiian and local San Diego surfer who is earning his doctorate at UCSD, Cliff Kapono, has been leading the charge in analysing microbial composition in surfers. Heading the Surfer Biome Project, he’s collected more than 500 samples by rubbing cotton-tipped swabs over heads, mouths, ears and every other part of surfers’ bodies, including their boards, for research.

Kapono, on the field for research. Photo courtesy of The New York Times.

Using a process called mass spectrometry, Cliff is able to create v-high quality maps of chemical metabolites with each sample. “We have the ability to see the molecular world,” he told The New York Times. “Whether it’s bacteria, or a fungus, or the chemical molecules.

With the aforementioned UCSD Center for Microbiome Innovation a quick trip across the quad for Cliff, he and his colleagues have been able to sequence and map the microbes to the best of their well-researched knowledgeability.

“A lot of research on the transmission of resistant bacteria has focused on the role of the health care environment,” Anne Leonard, an environmental epidemiologist at the University of Exeter who is also analysing whether surfers have higher rates of bacterial colonisation based on exposure, told The New York Times. “What’s less well studied is the role that natural environments play.”

Cliff and co.’s results from the lab have found evidence for the transfer of resistant genes from bacteria in the ocean into strains associated with the human gut when placed in close proximity. However, Cliff has yet to discover specific antibiotic-defiant extractions explicitly in his preliminary findings — derived from samples taken from surfers in California and Hawaii.

He plans on testing surfers in the South Pacific next, with Chile potentially on the books as well. The rural locations may yield some unique results.

Comments

Comments are a Stab Premium feature. Gotta join to talk shop.

Already a member? Sign In

Want to join? Sign Up